In the middle decades of the twentieth century, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) played a powerful role in big business’s crusade for authority in American life. Hoping to delegitimize the New Deal and labor unions, NAM embarked on a wide-ranging campaign to promote free enterprise.(1) This campaign involved a sustained deployment of visual-based propaganda in the workplace and public spaces, and was informed by the belief that habitual exposure to emotion-laden messaging could have a “constructive” effect on viewers’ dispositions.

NAM’s records, held at the Hagley Library, offer abundant insight into the organization’s visual propaganda campaign. Its main propaganda agency, the National Industrial Information Council (NIIC), was largely responsible for orchestrating its publicity. NIIC circulated 2 million copies of cartoons, 4.5 million copies of newspaper columns written by pro-business economists, 2.4 million foreign language news pieces and 11 million employee leaflets. It also displayed 45,000 billboards, which were seen by an estimated 65 million Americans daily, while its film series was viewed by approximately 18 million.(2) The 1938 advertisement below depicts some of these techniques, including movies, sound slide films, wage packet inserts, press releases and cartoons.(3) These “services” as NAM called them allowed employers to incorporate free enterprise discourse into the everyday life of the workplace.

This page from a 1938 NAM magazine reveals the breadth of its motivational techniques. It depicts nine major programs through which to “build goodwill for your local industry”—a euphemism for weakening labor union support and making workers more cooperative with management. Used in the workplace and in other venues in industrial areas, these communication methods offered NAM a powerful way to promote free enterprise to workers and the broader public.

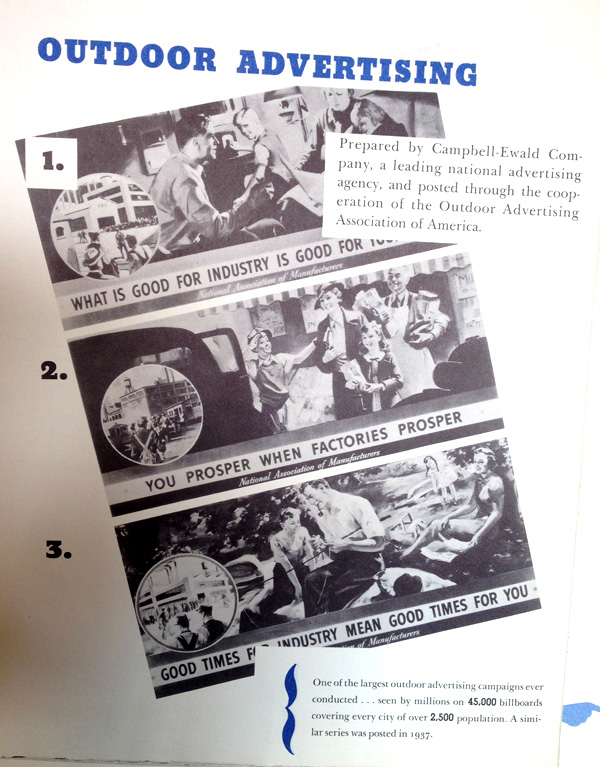

The next two images typify NAM’s use of emotion-driven visual propaganda. The first is an advertisement in a 1938 NAM publication that touts the benefits of its billboards (figure 2). The billboards were designed by the Campbell-Ewald Company, whose expertise in advertising design offered NAM a level of sophistication that it formerly lacked. With the aid of the Outdoor Advertising Association of America, NAM displayed its billboards in cities with populations of 2,500 and more in 1937 and 1938. NAM was under no illusion that publicity of this sort could prompt viewers to consciously accept the posters’ claims. Instead, it worked on the idea, then popular among communication theorists, that repeated exposure to emotionally stimulating messages could influence viewers on a subconscious level.

This page from a 1938 NIIC promotional booklet showcased NAM’s billboards to managers. NAM displayed thousands of these billboards in American towns and cities in the late 1930s.

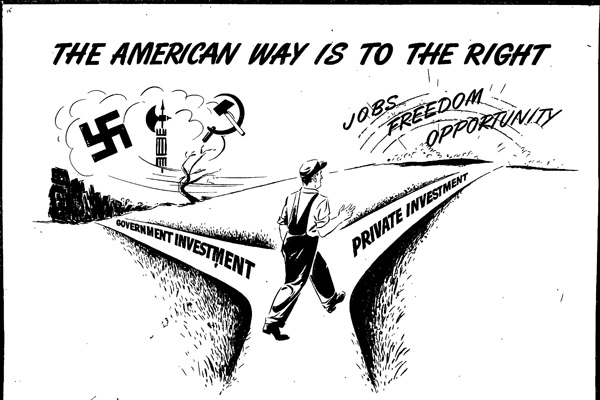

The final image is an advertisement placed in newspapers by NIIC toward the end of World War II.(5) With the postwar era on the horizon, NIIC intensified its criticism of the New Deal. The result was an effort to liken the New Deal to “slavery” while upholding free enterprise as a route to "freedom." An internal NIIC report in 1944 noted, “To convince people that freedom versus slavery is the issue, requires us to convince them that President Roosevelt or the bureaucrats (or any other group of personalities with whose ideology we take issue) desire to make people into slaves.” The author lamented, however, that while such rhetoric reinforced the opinions of NAM’s existing supporters, it “makes few converts . . . from the tremendous number of ‘middle-of-the-roaders’ who hold the balance of power and should be our primary audience.” He noted that, unfortunately for NAM, this group “believes that we are free men.” The solution to this problem, he concluded, was for NIIC to equate the rhetoric of Roosevelt and the New Deal with the “Directives, Orders, Bureaucratic planning [and] Mandates” used by Nazi leaders on their soldiers. As we see in this advertisement, NAM conflated the New Deal (symbolized by “government investment”) with Nazism and communism at the same time. Thus, even before the war was over, NAM was grouping one of the United States’ allies—the Soviet Union—in with fascists in an effort to delegitimize the New Deal. This tactic contradicted official wartime rhetoric claiming that the Russians were “just like us.”

An advertisement circulated by NAM in newspapers toward the end of World War II. In correlating “government investment” (a euphemism for the New Deal in NAM’s schema) with totalitarianism, and defining “private investment” as the route to “Jobs” “Freedom” and “Opportunity,” the ad offered its viewers a clear rationale for the need to replace the New Deal with a business-led economy.

Viewed together, this small selection of images helps to illustrate NAM’s increasingly skillful use of visual propaganda in the Depression and World War II. Its posters, advertisements, films and other forms of visual communication constituted a powerful apparatus through which to assert its pro-business agenda. NAM was far from the only organization to deploy visual propaganda in business’s campaign for authority during this era. Such techniques became standard for employee-motivation specialists and many employers once the U.S. entered the war. Still, as one of the most powerful business organizations of the 1930s and 1940s, NAM helped to establish some of the major rhetorical and design principles that other business organizations deployed in their efforts to assuage the appeal of the New Deal and labor unions and for years to come.

NOTES:

(1) For a comprehensive account of NAM’s crusade for authority, see Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Selling Free Enterprise: The Business Assault on Labor and Liberalism, 1945-1960 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

(2) The first four figures are stated in Sharon Beder, Free Market Missionaries: The Corporate Manipulation of Community Values (New York: Earthscan, 2006), 17. The number of billboard poster installations is from “Experts All: Who’s Behind Industry’s Public Relations Program,” folder: “Miscellaneous NIIC Material, 1938-1940,” box 848, series I, National Association of Manufacturers collection, Hagley Museum and Library. The figure for billboard viewings is quoted from William L. Bird, A Better Living: Advertising, Media, and the New Vocabulary of Business Leadership, 1935-1955 (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1999), 222.

(3) “For Use in Your Community: 14 Tested Means to Build Goodwill for your Local Industry,” folder: “Industrial Relations Community Prog.,” box 111, series I, National Association of Manufacturers collection, Hagley Museum and Library.

(4) “Experts All: Who’s Behind Industry’s Public Relations Program,” folder: “Miscellaneous NIIC Material, 1938-1940,” box 848, series I, National Association of Manufacturers collection, Hagley Museum and Library.

(5) “The American Way is to the Right,” folder: “Capital Formation,” box 843, series I, National Association of Manufacturers collection, Hagley Museum and Library.

(6) Letter, March 14, 1944. folder: “January—May 1944,” box 843, series III, National Association of Manufacturers collection, Hagley Museum and Library.

David Gray is a Visiting Assistant Professor in American Studies at Oklahoma State University. His book, Inventing the Motivational Workplace: Capitalist Communication and Management’s Crusade for Authority, is under review at Illinois University Press.