The term "patent medicine" has become particularly associated with drug compounds in the 18th and 19th centuries, sold with colorful names and even more colorful claims.

In ancient times, such medicines were called nostrum remedium, "our remedy" in Latin, hence the name "nostrum." Also known as proprietary medicines, these concoctions were, for the most part, trademarked medicines but not patented.

Origins of Patent Medicine

Patent medicines originally referred to medications whose ingredients had been granted government protection for exclusivity. In actuality, the recipes of most 19th century patent medicines were not officially patented. Most producers (often small family operations) used ingredients quite similar to their competitors—vegetable extracts laced with ample doses of alcohol.

Proprietary, or "quack" medicines could be deadly, since there was no regulation on their ingredients. They were medicines with questionable effectiveness whose contents were usually kept secret.

Originating in England as proprietary medicines manufactured under grants, or "patents of royal favor," to those who provided medicine to the Royal Family, these medicines were exported to America in the 18th century. Daffy's Elixir Salutis for "colic and griping," Dr. Bateman's Pectoral Drops, and John Hooper's Female Pills were some of the first English patent medicines to arrive in North America with the first settlers.

The medicines were sold by postmasters, goldsmiths, grocers, tailors and other local merchants.

Medicine Becomes an Industry

By the middle of the 19th century the manufacture of similar products had become a major industry in America. Often high in alcoholic content, these remedies were very popular with those who found this ingredient to be therapeutic.

Many concoctions were fortified with morphine, opium, or cocaine. Sadly, many of these concoctions were advertised for infants and children. Parents seeking relief for their babies from colic or fussiness often administered these remedies with tragic results.

Remedies were available for almost any ailment. These remedies were openly sold to the public and claimed to cure or prevent nearly every ailment known to man, including venereal diseases, tuberculosis, colic in infants, indigestion or dyspepsia, and even cancer. "Female complaints" were often the target of such remedies, offering hope for women to find relief from monthly discomforts.

From the beginning, some physicians and medical societies were critical of patent medicines. They argued that the remedies did not cure illnesses, discouraged the sick from seeking legitimate treatments, and caused alcohol and drug dependency.

The temperance movement of the late 19th century provided another voice of criticism, protesting the use of alcohol in the medicines. By the end of the 19th century, Americans favored laws to force manufacturers to disclose the remedies' ingredients and use more realistic language in their advertising.

These laws met with fierce resistance from the manufacturers.

Advertising

The Proprietary Association, a trade association of medicine producers, was founded in 1881. The Association was aided by the press, which had grown dependent on the money received from remedy advertising.

The pivotal event occurred when North Dakota passed a limited disclosure law, which included patent medicines. Proprietary Association members voted to remove their advertisements from all state newspapers.

With strong support from President Theodore Roosevelt, a Pure Food and Drug Act was passed by Congress in 1906. It paved the way for public health action against unlabeled or unsafe ingredients, misleading advertising, the practice of quackery, and similar rackets.

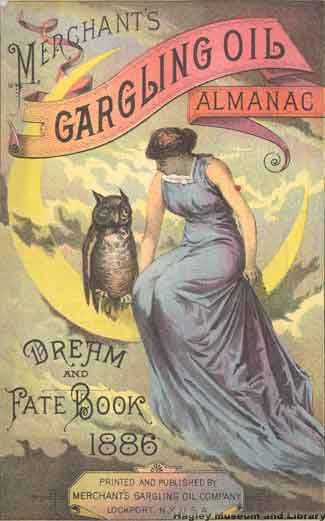

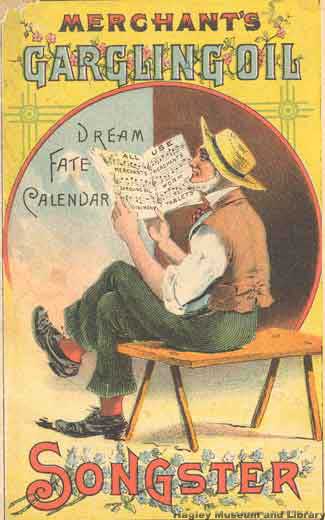

Images: Merchant's Gargling Oil Company, Lockport, New York.

For permission to reproduce or publish images, please contact research@hagley.org.