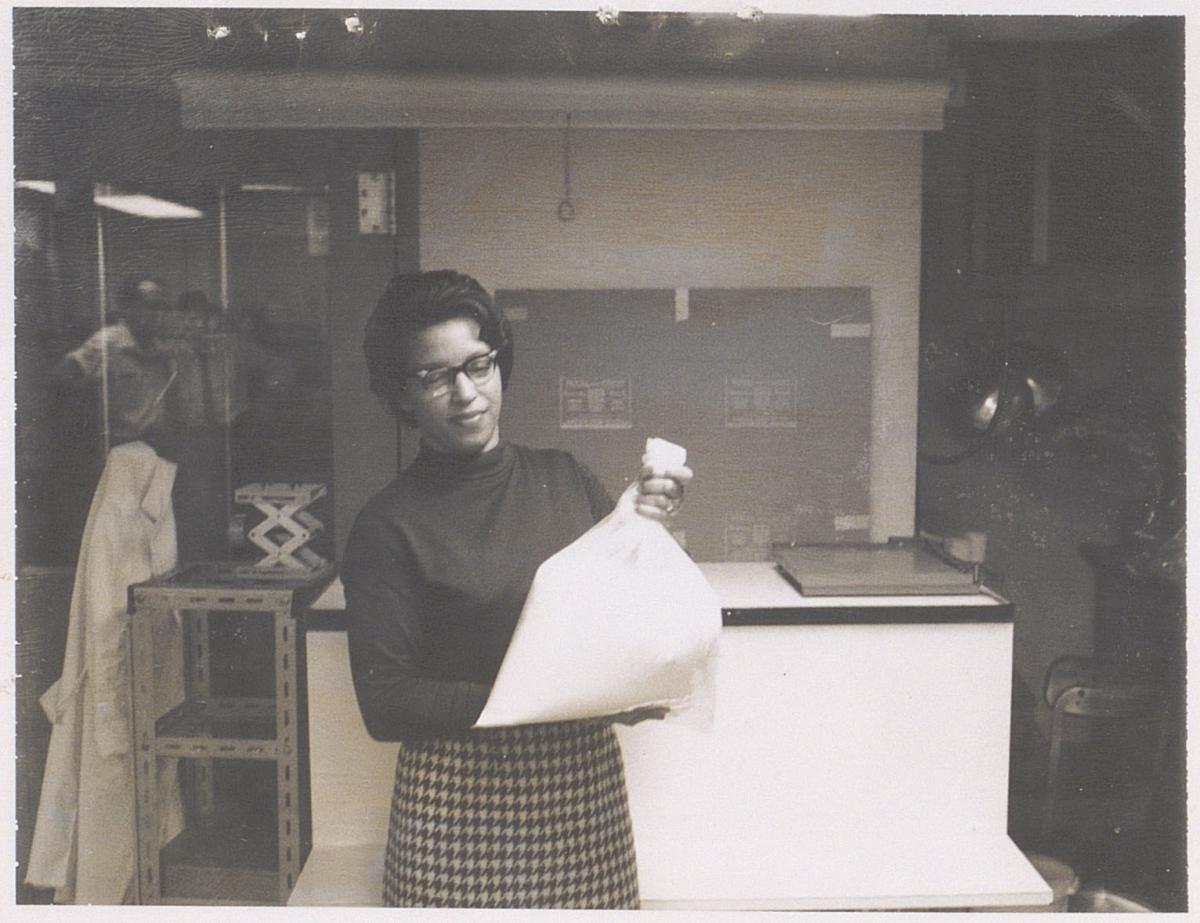

When looking for jobs, Rosetta Henderson faced discrimination from corporate recruiters, yet she persevered and received several offers before accepting a position with DuPont in 1965.

When looking for jobs, Rosetta Henderson faced discrimination from corporate recruiters, yet she persevered and received several offers before accepting a position with DuPont in 1965.

Before 1960, DuPont employed few Black workers, and even fewer were hired for “white collar” positions such as chemist, manager, and recruiter. Henderson joined DuPont just as the company was ramping up "equal opportunity" efforts in the early 1960s, a trend in corporate America following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and workplace discrimination protections created by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Photograph: A two-person lab at the DuPont Experimental Station in Wilmington, Delaware,1955. Hagley Digital Archives

From June 1, 1965, to July 1, 1968, DuPont added 1002 Black employees in the Wilmington area. Of these new employees, 402 were placed in “white-collar” positions, amounting to only 1.8% of such jobs within DuPont's local region. Though not listed by name in this report, Rosetta Henderson was one of the 402 since she was brought on as a chemist.

Despite the knowledge and talent Henderson and other Black employees contributed to the company, change at DuPont was piecemeal. In 1972, the company's Employee Relations Department presented a report recommending “action to improve recruitment, retention, and progression of minorities and women.” The report revealed that there were no Black or female employees at the upper-most salary levels in the company.

While DuPont reworked its hiring and recruiting practices, it continued to face external criticism for not speaking out against Wilmington’s housing policies and urban renewal projects, which destroyed working-class and majority-Black neighborhoods while restricting Black residents’ access to homes in desirable areas. When Rosetta Henderson arrived in 1965 as a new DuPont hire, she experienced firsthand the difficulty of finding housing in Wilmington as a Black woman. Wilmington remained a segregated city, so she initially stayed at the local YWCA which was the only integrated accommodation near her job at the DuPont Experimental Station. The YWCA of the U.S.A. began boarding houses for Black and Indigenous American women in the 1880s, with some accommodations integrating as early as the 1910s. In Wilmington, the King Street YWCA Delaware location was a safe space for Henderson because of the YWCA's early integration efforts and their commitment to stamping out racism.

Still, the YWCA was temporary housing, and Henderson was determined to find her own place. The racist zoning laws and landlords in the city meant that Henderson would only find an apartment after bringing her White supervisor and coworker along, giving prospective landlords the impression the rental was for them only for Henderson to sign the lease.

In this clip, she describes her job hunt after graduate school, getting the job with DuPont, and expands on her search for housing in segregated Wilmington, Delaware: