Zombies are a trending topic in popular culture. Movies and television series still build upon this genre of horror decades after George Romero filmed the movie Night of the Living Dead near my hometown in 1968. During the golden age of invention in the late nineteenth century, everyday folks like you and me were hard at work developing devices not to protect themselves from the dead, but to protect the dead from the living.

Grave robbing was a booming business in the Victorian Age. “Resurrectionists” as they were sometimes called, would sneak into cemeteries in the dead of night and exhume fresh graves. While the lure of a granddad’s diamond stick pin or grandmama’s cameo brooch was tempting, the real value lay in the body itself.

Grave robbing was a booming business in the Victorian Age. “Resurrectionists” as they were sometimes called, would sneak into cemeteries in the dead of night and exhume fresh graves. While the lure of a granddad’s diamond stick pin or grandmama’s cameo brooch was tempting, the real value lay in the body itself.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the study of medicine became less of an apprenticed trade and more of an occupation requiring rigorous university training. Growing enrollment in medical schools created a strong demand for corpses for dissection. The supply of donated or unclaimed bodies of paupers and executed criminals was soon exhausted, so independent contractors, or even the students themselves, grabbed their shovels and lanterns to fulfill the demand and earn a tidy profit.

Sensational stories of body snatching circulated in the newspapers throughout the 1870s and included engravings of resurrectionists such as the one to the right. One story in particular garnered national attention. Former U.S. Congressman John Scott Harrison—son of President William Henry Harrison and father to President Benjamin Harrison—died in North Bend, Ohio on May 25, 1878. Despite being buried in a cemented brick vault covered in soil mixed with heavy stones and the family hiring a watchman to check on the gravesite every hour through the night, his body was stolen. Harrison's family found his body at the Ohio Medical College in Cincinnati. The body of the man buried next to him was found preserved in a vat of brine at the University of Michigan Medical School.

While stealing corpses for profit was a centuries-old concept, the practice violated Victorian sensibilities regarding death and dying. This was a time of great religious morality where Christian burial practices demanded the body remain undisturbed until the Resurrection. Thanks to the recent advancement of embalming techniques, the body was preserved and treated with the utmost respect. Funeral homes offered the growing middle class, with their disposable income, elaborately decorated and sealed metal caskets with glass viewing ports. The term “casket," denoting a container for something precious and valuable, began to replace “coffin.” Churchyard burial grounds gave way to elaborately designed and landscaped memorial gardens where friends and relatives returned to visit the gravesites of the dearly departed. This was not a society that would allow loved ones to end up on the dissection table.

Inventors recognized the opportunity and patented various devices to ease their fears. Most were passive. These included heavy cast iron coffins, weighted anchoring systems, cages built over the graves called “mortsafes”, and hidden locking mechanisms on the caskets. Others were more aggressive, including “grave guns” that not only sounded an alarm but were intended to maim and possibly kill anyone who tried to disturb granny’s eternal rest.

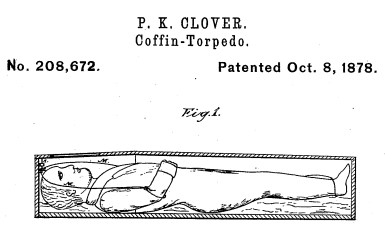

While cataloging recently, I discovered a patent model for one of these anti-personnel devices called a “coffin torpedo”. Those two words together create a confusing mental picture. We all know what a coffin is. We all know what a torpedo is. But what is a coffin torpedo?

Today, we think of a torpedo as something a submarine launches through the water to sink a ship. Are you familiar with the famous quote from Civil War Admiral David Farragut, who shouted, “Damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead”? A torpedo in the nineteenth century referred to a type of stationary explosive or mine.

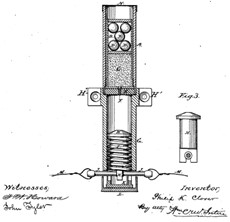

The coffin torpedo consisted of an iron pipe about six inches long containing a charge of gunpowder packed with metal balls. Trip wires ran from both sides of the bottom of the tube containing the trigger mechanism and were secured around the arms and ankles of the corpse. The device was mounted at the head of the coffin, recognizing that the thief would have to bend over the head and shoulders to lift the body of the casket. In doing so, the thief earned a face-full of buckshot. The sound of the discharge alone could scare away the robbers or alert the caretaker and passersby.

The coffin torpedo consisted of an iron pipe about six inches long containing a charge of gunpowder packed with metal balls. Trip wires ran from both sides of the bottom of the tube containing the trigger mechanism and were secured around the arms and ankles of the corpse. The device was mounted at the head of the coffin, recognizing that the thief would have to bend over the head and shoulders to lift the body of the casket. In doing so, the thief earned a face-full of buckshot. The sound of the discharge alone could scare away the robbers or alert the caretaker and passersby.

Philip K. Clover patented his coffin torpedo on October 8, 1878. He filed for his patent the month after the scandal around the theft of John Scott Harrison’s body. A well-known artist, he lived in Ohio, about a day’s train ride from where Harrison was buried.

Did these contraptions work? Yes! In January 1881, one of these devices killed a graverobber in Mount Vernon, Ohio, who went by the rather appropriate name of “Dipper”. Of his two accomplices, one suffered a broken leg. The other wrestled him into a sleigh and escaped but were apprehended later.

Historical and archaeological evidence suggests that few coffin torpedoes were sold, and they, like most inventions patented in the nineteenth century, represent more of a gimmick than a useful product. This was not from a lack of marketing by the inventors. One advertisement for Thomas Howell’s Grave Torpedo read:

Sleep well sweet angel, let no fears of ghouls disturb thy rest, for above thy shrouded form lies a torpedo, ready to make minced meat of anyone who attempts to convey you to the pickling vat…”

So, this Halloween, those of you with a fear of zombies, fret not. The living are always more dangerous than the dead.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library