I came to the Hagley Library on a research grant last summer to carry out preparatory research for my dissertation on French trading migrations in the Ohio Valley between 1789 and 1815. There, nestled in a long series of correspondence between members of the du Pont family and Waldemard Mentelle, a French emigrant in Lexington, Kentucky, I stumbled across a map of Kentucky lands that piqued my interest. Uncovering the story of these documents helped me understand the challenges and rewards of trading efforts at this time.

Pierre-Samuel du Pont de Nemours arrived in America on January 1, 1800 in Newport, Rhode Island. As a physiocrat, he believed that the earth was the fundamental source of wealth and that the economy rested entirely on agriculture. He was hoping to establish an agricultural colony whose love of humanity would be the natural law. He planned to name it “Numa.”

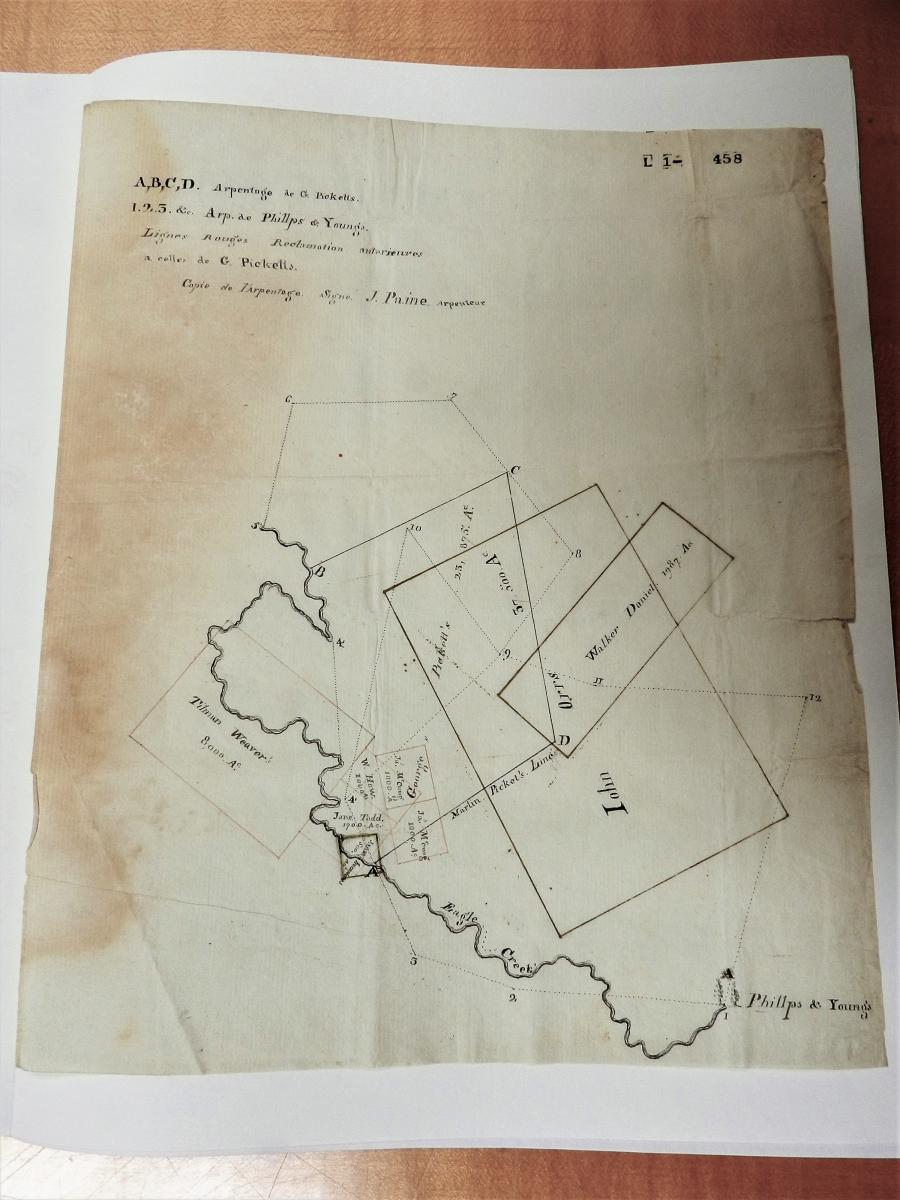

To realize this ambition, du Pont created a company in Paris with a share capital of four million francs to speculate on the purchase and resale of land in America, and to trade commission with offices in Alexandria and New York managed by another member of the family. One of the first things du Pont did when he arrived in America was to buy, in the name of his son Victor and for the sum of two thousand dollars, lands in Kentucky which had been sold for non-payment of taxes. Clearly du Pont hoped to found his colony on the banks of Eagle Creek in the Ohio Valley.

Du Pont needed an agent on the ground to assess the land and keep up with tax payments, so he reached out to Waldemard Mentelle, the son of one of his colleagues at the Paris Institute, who was living in Lexington, Kentucky. Mentelle visited the property, made a survey, and weighed in on the land’s agricultural prospects: “The soil is usually mixed with hills; we call it broken land.”

But du Pont’s other duties quickly sidelined his agricultural project. When he left for Europe to negotiate the purchase of Louisiana, Mentelle directed his correspondence to Pierre-Samuel’s son, Victor-Marie. While he continued to pay taxes on the du Ponts’ behalf, Mentelle tried to make good on the property. He worked with the county surveyor to propose dividing the lands into 21 properties that could be sold at a profit. But Victor-Marie was less interested than his father in the family’s Kentucky landholdings, and eventually the du Ponts’ bankers stopped payment on the land taxes. The correspondence between Victor du Pont and Waldemard Mentelle ceased, and the colony of Numa remained an unfulfilled dream.

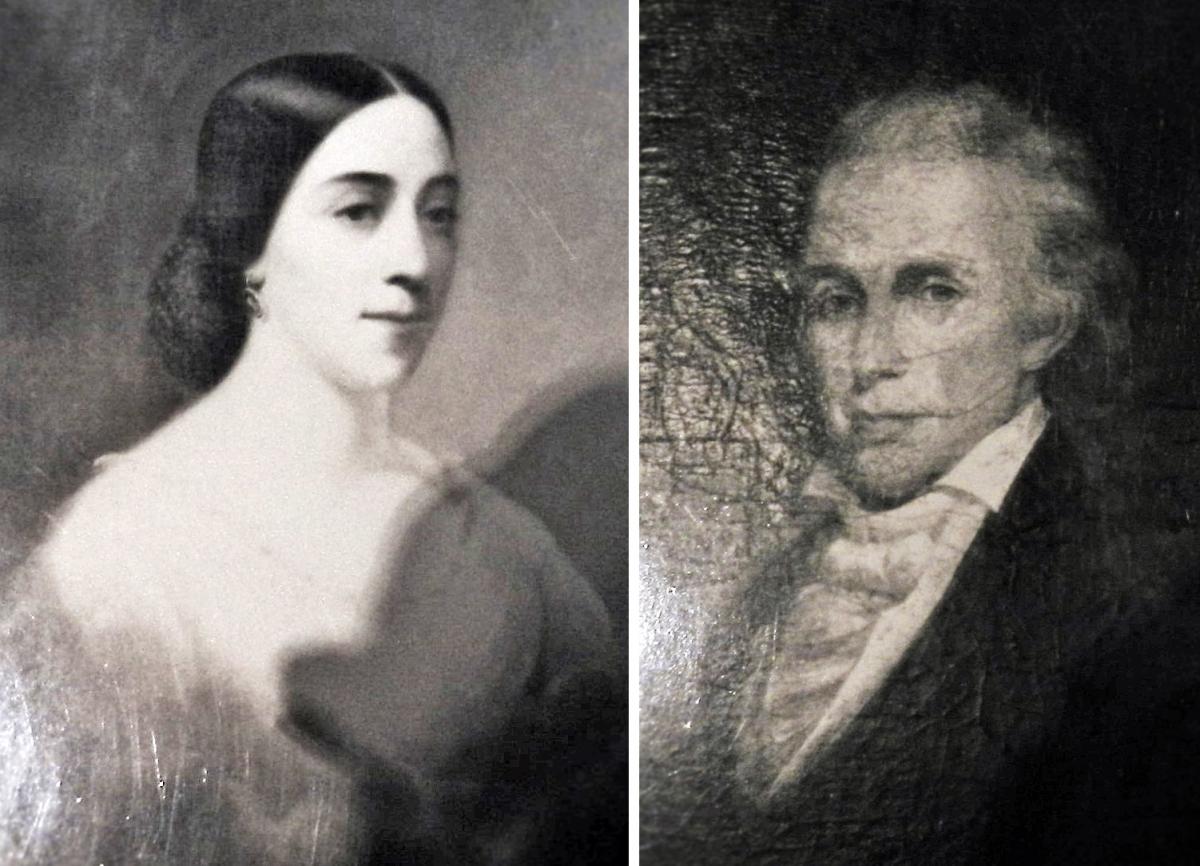

Despite Numa’s failure, Mentelle was eventually successful in his Ohio Valley ventures. He later opened a commission store and then incorporated the U.S. Branch Bank of Lexington. His wife, Charlotte, founded a boarding school for young ladies whose most famous pupil was Mary Todd Lincoln. The map of du Pont’s Kentucky lands is a moving testimony, not only to du Pont’s physiocratic project, but also to the challenges migrants like the Mentelles faced in America during this period of rapid change.

Marcel Deperne is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of La Rochelle in France. He came to Hagley in the summer of 2017 on an H. B. du Pont Research Fellowship from the Center for the History of Business, Technology, and Society. His dissertation is entitled “Atlantic Networks in the Ohio River Valley: French Merchants from Pittsburgh, PA to Henderson, KY, 1789–1815.”