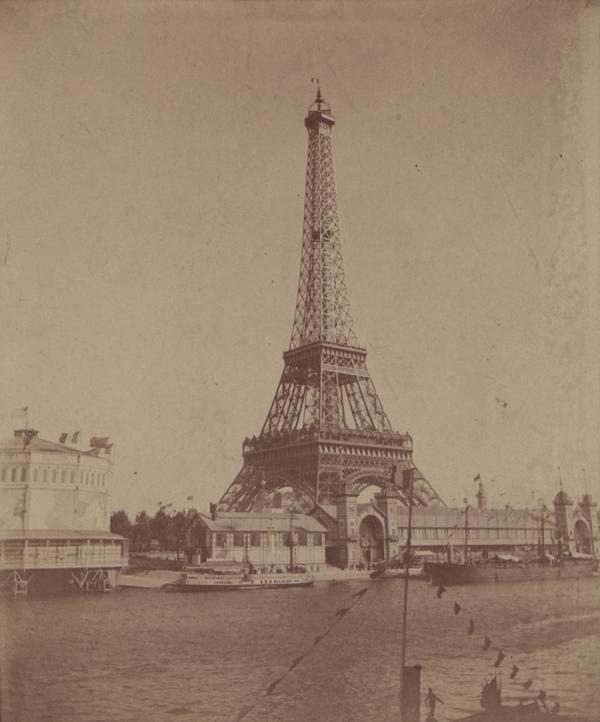

On January 26, 1887, the first digging work began on the construction of what would become the Eiffel Tower. It would take two years, two months, and five days before the massive structure was complete.

In 1884, Paris officials began planning for a “universal” exposition that, following the regular 11-year interval for world’s fairs, would take place in 1889 and happened to coincide with the centennial of the French Revolution. The officials agreed that the fair should feature a single signature structure, something special that would act as a symbol of French culture. The Committee proposed that this symbol should be a 300-meter tower, the tallest structure ever built. Over 100 tower designs were received, including a giant guillotine!

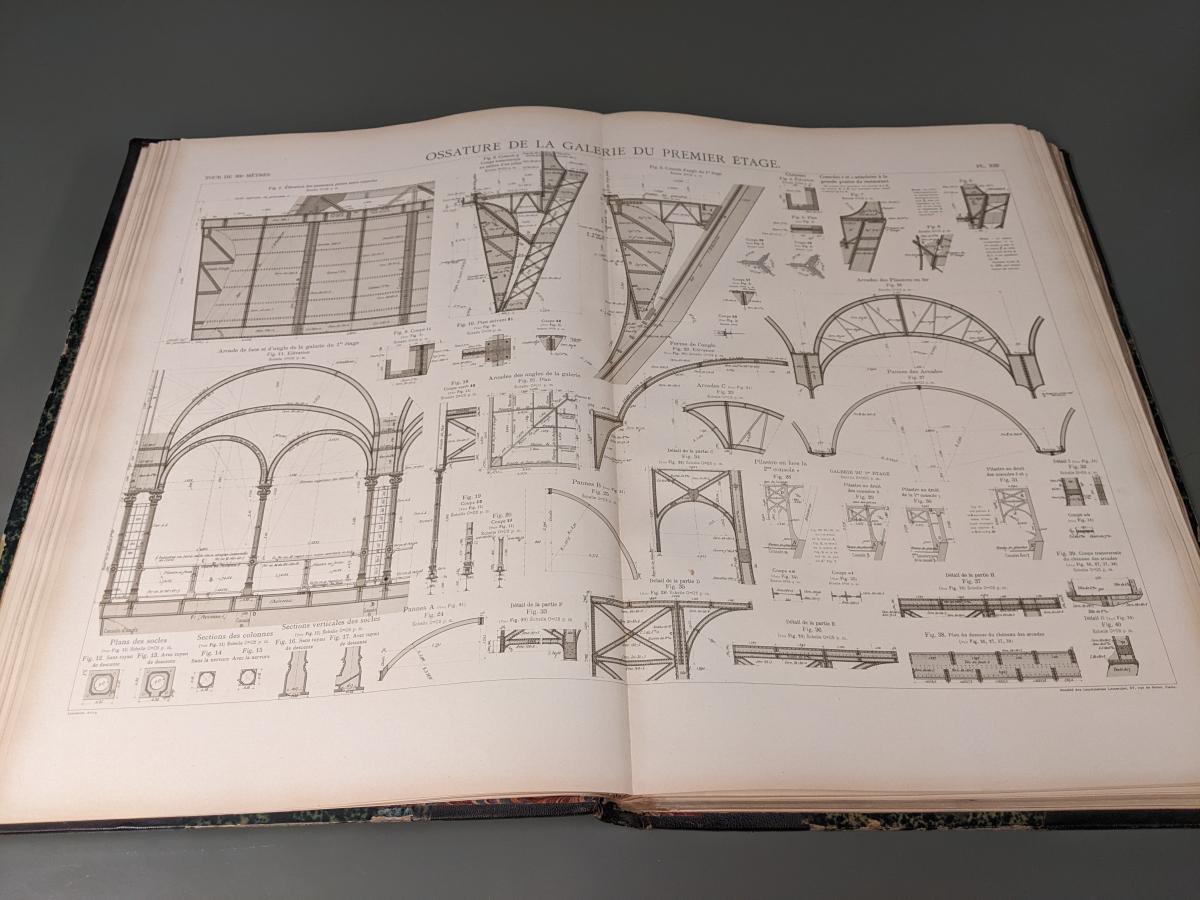

At the time of the competition, Gustave Eiffel was already regarded as one of the leading engineers of the time, particularly known for his bridges. On September 18, 1884, Eiffel registered a patent for "a new configuration allowing the construction of metal supports and pylons capable of exceeding a height of 300 metres." The wrought-iron lattice designed by Gustave Eiffel, along with engineers Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier and architect Stephen Sauvestre, was accepted.

While Eiffel was awarded the contract, he was dismayed to learn that he would only be funded for less than one-fourth of the projected costs. He funded the rest of the cost himself while signing an agreement that would give him income from the Tower for twenty years.

According to the official website of the Eiffel Tower,

All the elements were prepared in Eiffel’s factory located at Levallois-Perret on the outskirts of Paris. Each of the 18,000 pieces used to construct the Tower were specifically designed and calculated, traced out to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimetre and then put together forming new pieces around five metres each. A team of constructors, who had worked on the great metal viaduct projects, were responsible for the 150 to 300 workers on site assembling this gigantic erector set.

Citizens of Paris watched the construction of the Eiffel Tower over two years with mixed feelings. Some of the leading artists and writers protested the tower as an “abomination and eyesore,” but not even Eiffel himself expected the intense interest that the tower would inspire.

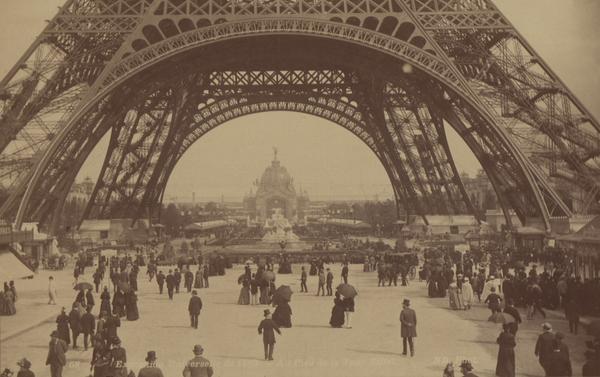

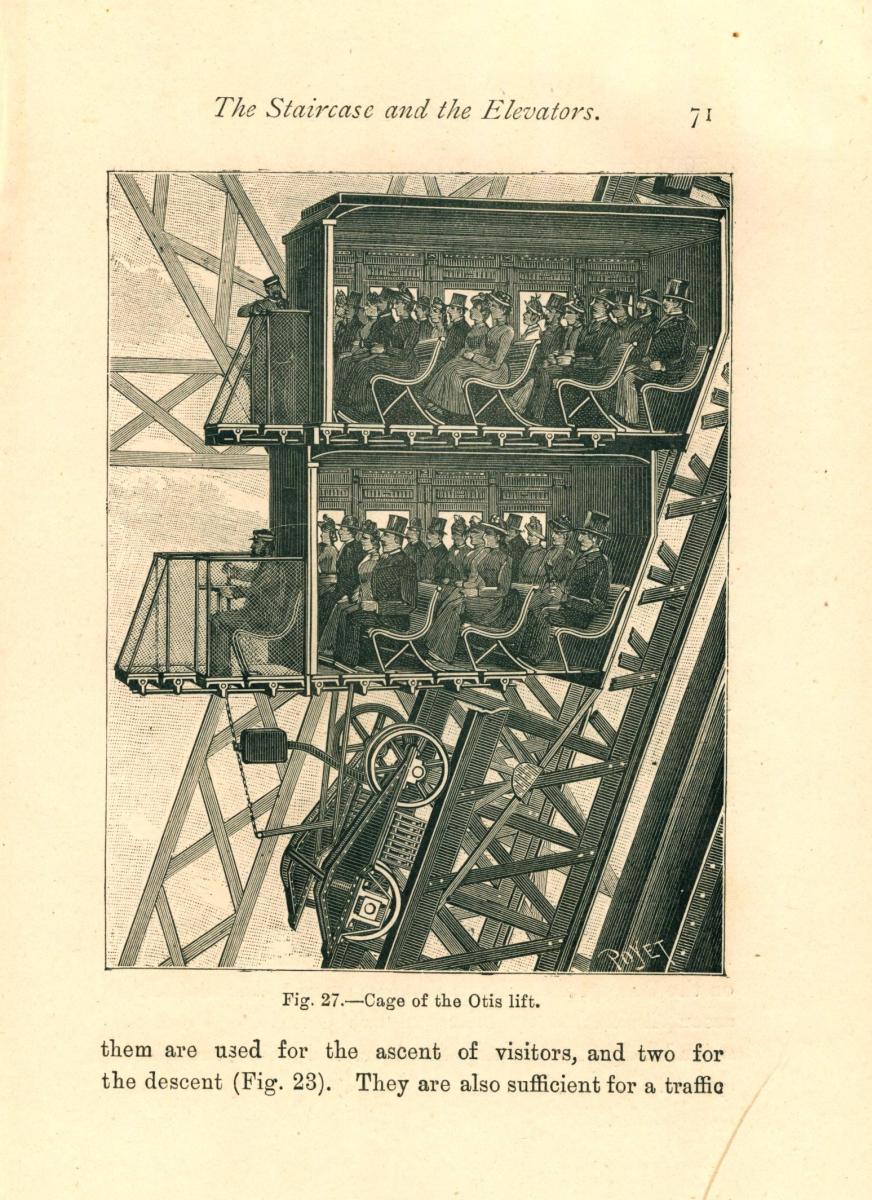

The Exposition Universelle de 1889 was held from May 5 to October 31, 1889 and attracted more than 32 million visitors. Almost two million people paid to ascend Eiffel's Tower during the fair, equal to about 20,000 people daily waiting to use the five elevators that would take them to the top. The curvature of the Tower’s legs imposed a problem unique to elevator design, and no French companies were able to provide the technology for this needed feature.

The Exposition Universelle de 1889 was held from May 5 to October 31, 1889 and attracted more than 32 million visitors. Almost two million people paid to ascend Eiffel's Tower during the fair, equal to about 20,000 people daily waiting to use the five elevators that would take them to the top. The curvature of the Tower’s legs imposed a problem unique to elevator design, and no French companies were able to provide the technology for this needed feature.

The American Otis Brothers & Company did submit a proposal through its Paris office, Otis Ascenseur Cie., but the fair’s charter prohibited the use of any foreign material in the construction of the Tower. Finally, in desperation, the Commission awarded the contract to Otis in July 1887.

Four restaurants were housed on the Tower's first floor, each featuring a different cuisine: the Russian restaurant, the Anglo-American bar, the French restaurant, and the Flemish restaurant.

Tickets cost two francs to ascend to the first level, three for the second, and five for the top, with half-price admission on Sundays. The gamble to foot the bill for the construction of the tower paid off, and Eiffel made a lot of money from this venture.

Thomas Edison had a display at the fair, and his incandescent light bulb made it possible to keep the fair open at night. The Tower itself was capped by a tricolor searchlight that lit up half of the city.

Thomas Edison had a display at the fair, and his incandescent light bulb made it possible to keep the fair open at night. The Tower itself was capped by a tricolor searchlight that lit up half of the city.

Originally, the Tower was only supposed to stand for twenty years. Part of the original contest rules for designing the Tower was that it should be easy to dismantle. This was to happen in 1909 when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris. Luckily, the Tower was important as a radiotelegraphic station, so it was able to live on through the 1900 Paris fair and beyond. It’s now perhaps the most recognizable symbol of Paris.

The Eiffel Tower remained the world's highest construction until the Chrysler Building was erected in New York in 1930.

Hagley Library holds a number of items related to the 1899 World’s Fair and the Eiffel Tower, including two rare, oversized volumes containing copies of Gustave Eiffel’s original blueprints, La tour de trois cents mètres / G. Eiffel. Paris : Société des Imprimeries Lemercier, 1900.

Here is a link to a digitized version of the volume of plates (planches) from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Here is a link to another item that can be found in our digital archive.

To search our online catalog for materials related to the Fair or the Eiffel Tower, you can use the searches below:

- Exposition universelle de 1889 (Paris, France)

For more information about making an appointment to see these materials or others at the Hagley Library, please read about our Research Services.

Linda Gross is the Reference Librarian in the Published Collections Department at Hagley Museum and Library.

Additional Image Captions and Attributions

- Image 2, Otis Elevator, from Hagley Library.

- Image 4, The Eiffel Tower at night during the Paris Exposition, 1889, from the Library of Congress.