My dissertation, “All the Comforts of Hell: Doughboys and American Mass Culture in the First World War,” argues that American soldiers used the scale and scope of their needs during World War I to push army officers and welfare secretaries to reshape all facets of the country’s mass culture. Mass conscription created an unprecedented army marked by the racial, ethnic, and class diversity of four million recruits, and progressive administrators from seven welfare organizations and the War Department organized entertainment and morale programs on their behalf. My analysis expands beyond interpretations of wartime welfare as an effort to remake young men or replicate middle-class lifestyles, instead borrowing approaches from business and consumer history to illustrate individuals’ ability to reshape institutions. Placing soldiers at the center of these programs ultimately provides a more accurate portrait of the social history of the military while also demonstrating the dynamic potential of mass culture.

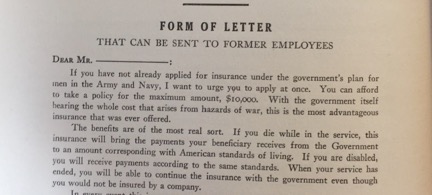

During my time at Hagley funded by an Exploratory Research Grant, I studied the Chamber of Commerce of the United States records. In the Chamber’s minutes and publications, I discovered its leadership actively supported the government’s War Risk Insurance program. In the early twentieth century, Progressive officials believed the robust pensions the federal government provided to Civil War veterans were actually a flawed policy that committed the federal government to unwise long-term expenses. As a result, a major benefit the government provided to soldiers was War Risk Insurance; the federal government sold insurance to soldiers at subsidized rates comparable to what they would pay if they were not serving in the military. Such a program encouraged conscripts from a variety of backgrounds to both embrace insurance as an important consumer good and perceive the benefits of providing personal data to salesmen and the federal government. The Chamber of Commerce actively encouraged members to promote this program, asking members to send letters to former employees now enlisted in the military to take advantage of the program.

now in the military to purchase government-subsidized insurance.

(Chamber of Commerce of the United States, Accession 1960, box 60, Hagley Museum and Library)

Through my prior research at other archives, I connected these Chamber advertisements to soldiers’ sentiments about the program. John J. Barada learned about the program from his commanding officer and was impressed by its potential benefits, deciding to take out the maximum policy. Others such as Walter Shaw faced the dangers of war and knew the program could help, contemplating the philosophical dilemma that made him “worth more dead than alive.” Following the armistice, The Stars and Stripes reported that over four million soldiers and sailors had purchased insurance policies valued over $40 billion through the program.

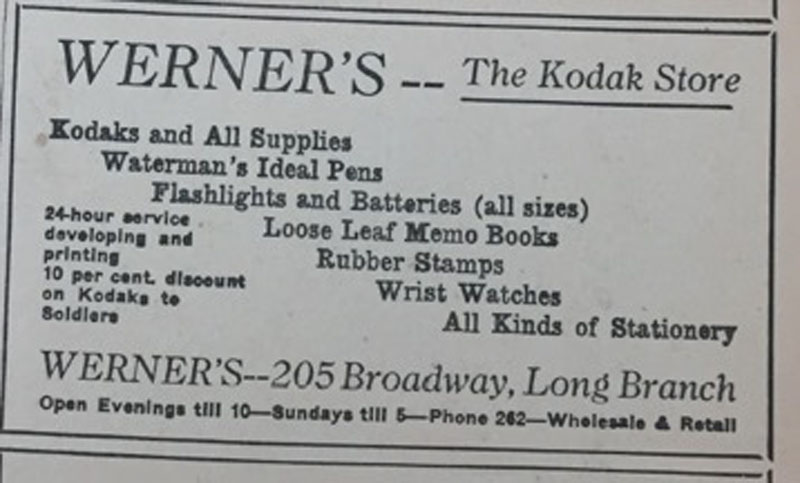

I continued my research in Hagley’s collection of trade literature and histories on several American companies that produced goods marketed towards soldiers during World War I. Through these materials, I learned about several companies that marketed their products to soldiers. For example, Eastman Kodak marketed its Vest Pocket Autographic Kodak camera to soldiers’ families as a gift that could alleviate the boredom of training camp life.

Kodak offered a product so popular soldiers disregarded Army rules

and covertly took pictures during their time in France.

(YMCA Armed Services Department: An Inventory of Its World War I Records,

box 140, Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota)

Although officially barred from taking pictures overseas, soldiers like Everett Kornegay and Lucien Cocke loved the camera and took it with them to France. The Kodak was popular enough that French retailers purchased advertisements in the Stars and Stripes encouraging soldiers to take advantage of new technologies and services, and some welfare huts sold Kodak film to soldiers that allowed troops to continue enjoying their hobby. Soldiers like Otis Emmons Briggs integrated their photographs into their memoirs, while others including Rex Bixby and Richard Crump collected their pictures into elaborate scrapbooks that demonstrated the camera’s obvious benefit allowing soldiers to create and store personal memories. By connecting corporate and personal sources, I demonstrate not just that companies like Kodak and the insurance industry hoped to win soldiers’ business, but also that perceived personal benefits encouraged the American public to embrace them.

I would like to thank the entire staff of the Hagley Library for their help. It was an honor receiving an Exploratory Research Grant, and I hope future scholars will continue to take advantage of Hagley’s excellent material and human resources.

Mark Hauser (@markhauser) recently completed his doctoral dissertation in the History Department at Carnegie Mellon University. His research interests include nineteenth- and twentieth-century US cultural history, popular culture, and consumerism.