The use of cash during the pandemic has plummeted in many countries. Although it might be early to tell if there has been a permanent shift to digital payments, lockdown and social distancing have certainly accelerated trends to reduce the number of bank branches and automated teller machines (ATMs).

Go back to the 1970s, when the world was very much a cash economy, ATMs were commonly known as cash dispensers. At that time, there were multiple manufacturers, and the devices clunky to operate and unreliable. Banks and other deposit-accepting financial institutions across the world looked at the new technology with great interest. It promises to be a solution for out-of-hours delivery of banknotes, enabling servicing a larger number of customers (as many adults did not have a bank account) and solving branch congestion issues.

The situation was perhaps more acute in the USA. Restrictions to geographic growth hampered following the most affluent customers in their migration to the suburbs, let alone business travelers across state lines. Regulatory changes had also enabled savings banks to start offering cheque accounts, the so-called NOW accounts. Delivering on these accounts meant investing in relevant skills and capabilities, such as cheque clearing and the capital-intensive ATM network. Moreover, in some states, such as Pennsylvania, the ATM was considered a bank branch and had to go through the same regulatory approval process.

The Hagley Museum and Archives have a very detailed collection of the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society or PSFS (accession 2062, Box 13), at the time the biggest savings bank in the USA in terms of assets. This collection spans almost 200 years worth of business records up to the organization's demise in the mid-1980s. A travel grant was awarded in 2007 to explore these records, primarily around issues of corporate strategy and adoption of technological devices leading to the deployment of ATMs in 1981.

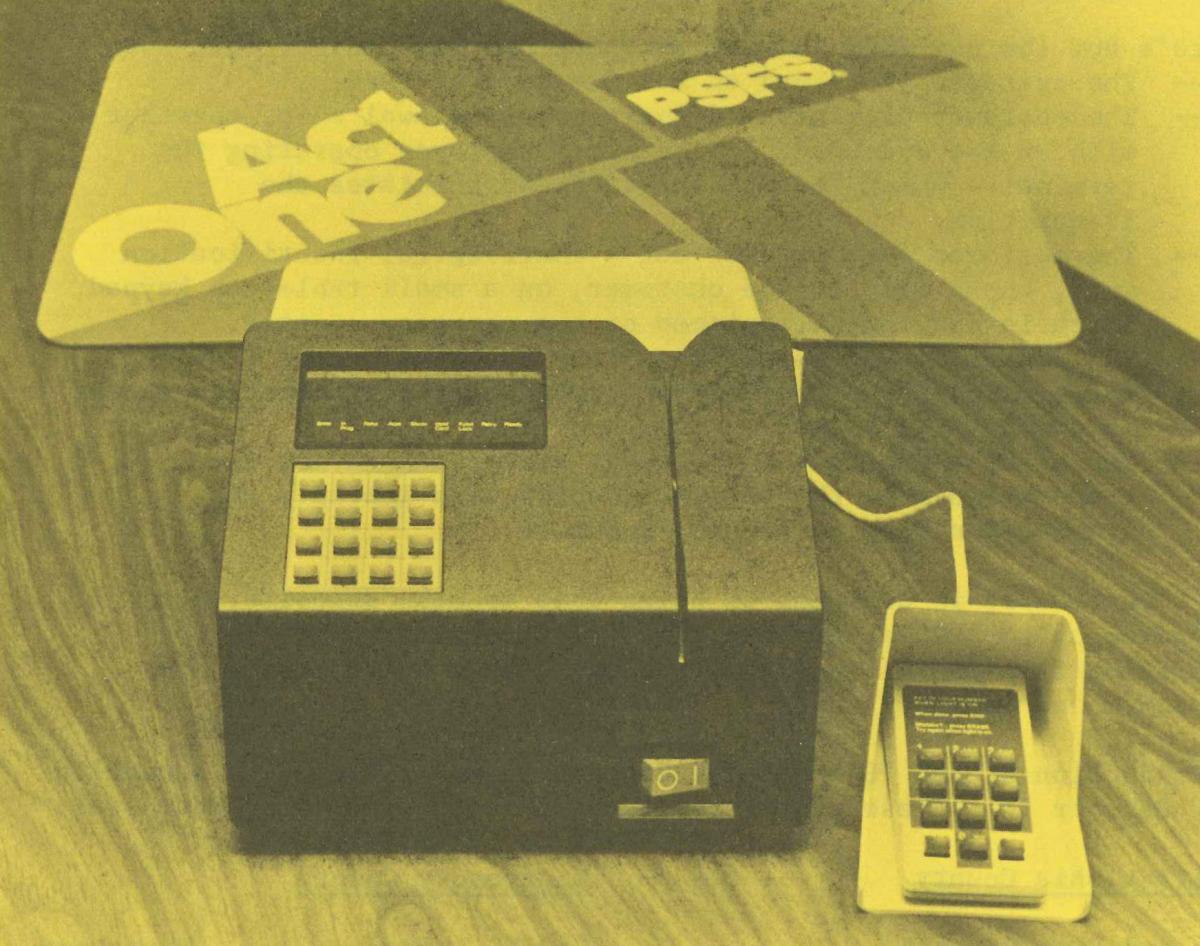

Interestingly, there was quite a bit of debate within the PSFS before the adoption of ATMs. At the time, the PSFS had some 75 retail branches. This number was minuscule when compared with a couple of thousands at Lloyds Bank in the UK. Surprisingly, instead of committing to large capital investment in ATMs, like other savings banks, the PSFS supported the roll-out of NOW accounts (commercialized as "Act One") with a device sometimes known as "Hinky Dinky."

The moniker came from the first trial of these devices in April of 1974, between the First Federal Savings & Loan Association and the Hinky Dinky chain (part of American Community Stores) in Lincoln, Nebraska. The Federal Home Loan Bank Board supported the move as an experiment in remote Electronic Fund Transfer. But, the case in Nebraska had its history of legal challenges.

Since under regulation, the savings banks were unable to issue personal loans and therefore overdrafts. Just like an online ATM, the Hinky Dinky devices promised to enable verification, recording transactions, and updating accounts directly with the bank on the spot.

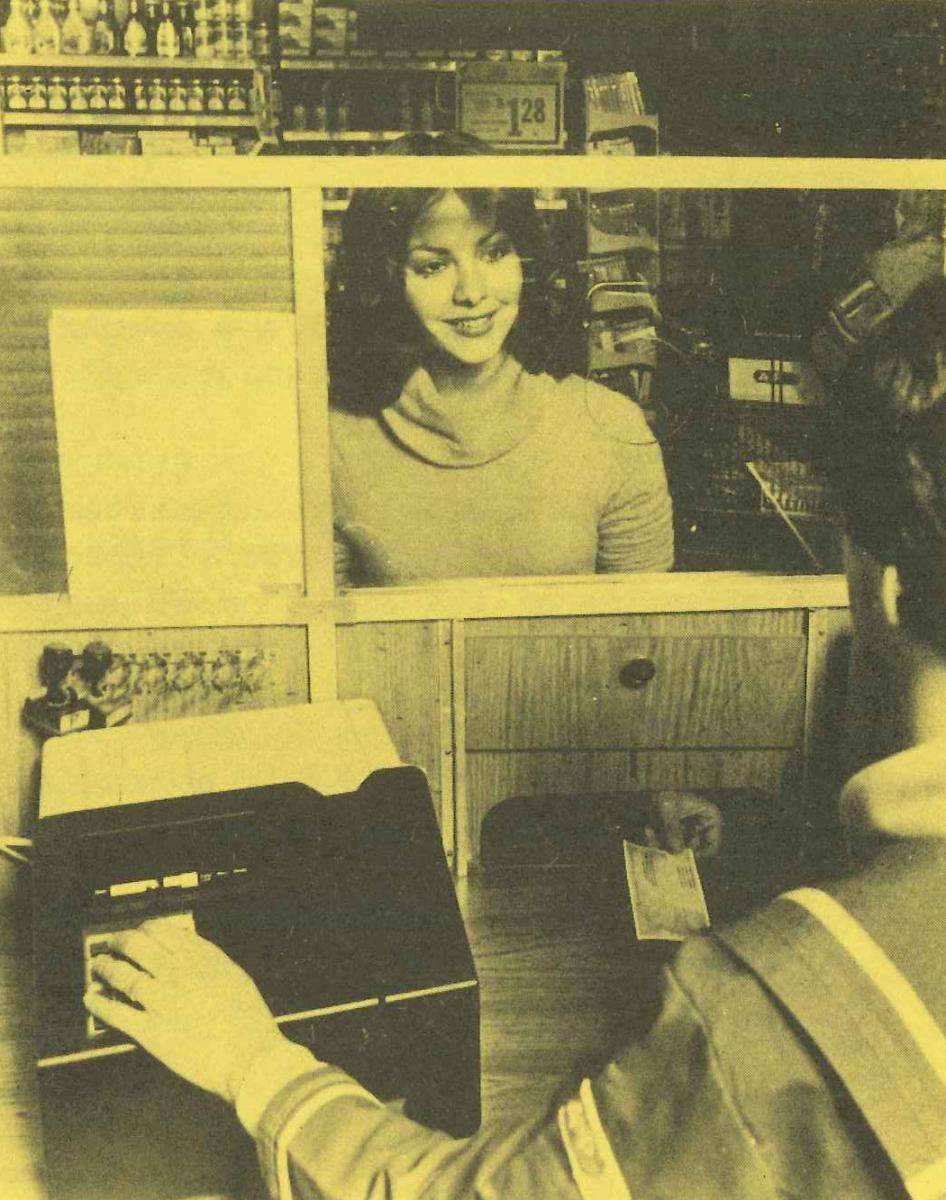

As the image shows and had been the case in Nebraska, the Hinky Dinky was a low-tech, cheque cashing device, which read the magnetic characters in the cheque, activated by a personal plastic card. PSFS made a strategic alliance with A&P Stores in 1979. The idea was to locate "islands" or "courtesy booths" (promoted as ActOne Personal Banking Centres) within the A&P retail space. These booths provided PSFS customers convenient access to cash and other everyday banking transactions while shopping at A&P stores in Philadelphia, Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware Counties. The booths were operated by A&P personnel "experienced in processing banking transactions with the terminals."

The PSFS and other savings banks were able to deploy these "point of sale" devices by successfully arguing that neither the devices nor the booths retained deposits or lent funds. More importantly, the retailer was portrayed as only "a conduit, [as] much as the Post Office might for deposits and withdrawals by mail."

However, the Hinky Dinky terminals were prone to abuse. By 1981 the PSFS decided to end the service and replace the stalls with the now more affordable and tested ATM.

The events surrounding the deployment of Hinky Dinky terminals by PSFS seem rather peculiar. It promises to shed light not only on the pursuit of suburban customers but retail banks but also to question the strategies of retailers and their disposition to collaborate with financial institutions.

Today, many food retailers have developed a banking arm, as is the case of Tesco in the UK and Walmart in Mexico. Meanwhile, before COVID, supermarket forecourts were one of the most active and long-standing locations for ATMs. The peculiar case of Hinky Dinky was, in a way, a precursor of these developments and perhaps worthy of enquiring the archives again.

Dr. Bernardo Batiz-Lazo is a business and economic historian and professor in the Newcastle Business School at Northumbria University. To support his research, Dr. Batiz-Lazo received grants from the Center for the History of Business, Technology, & Society at the Hagley Museum & Library.