In the nineteenth century, where a train stopped was as important as where it went. My dissertation focuses not on the long lines that bound the continent together, but the large urban train stations that spread over acres of American cities in the late 1800s. My research at Hagley was an attempt to uncover the social life that existed in and around these urban terminals.

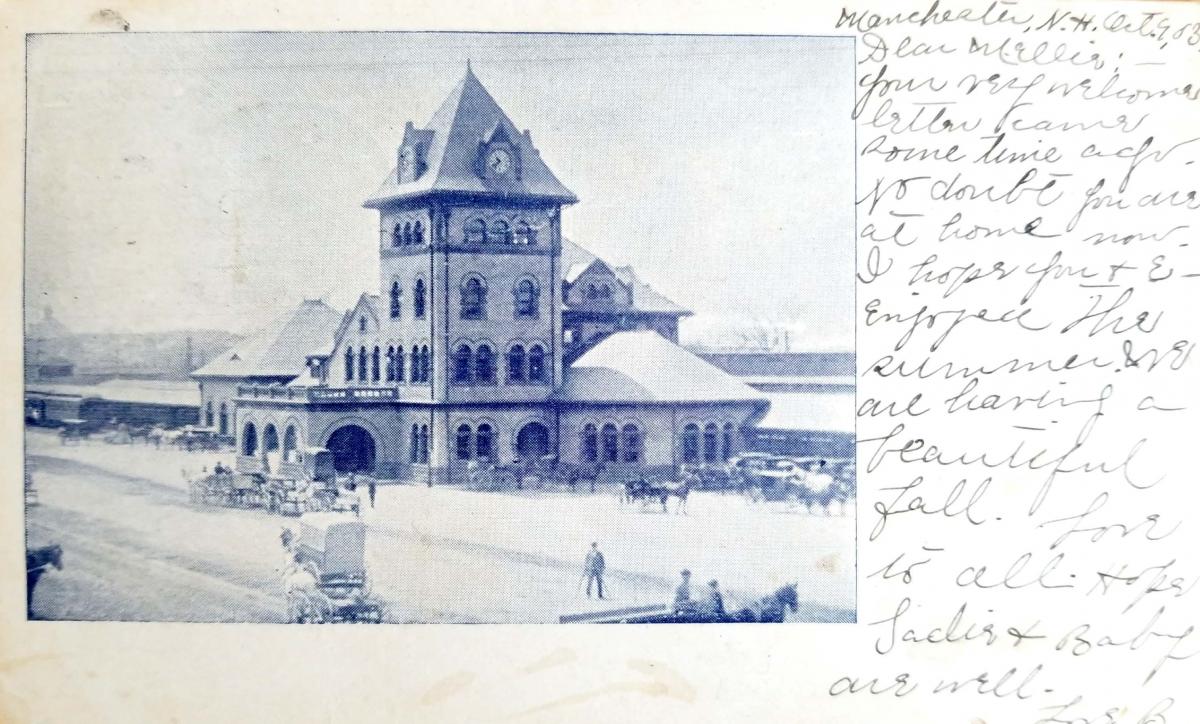

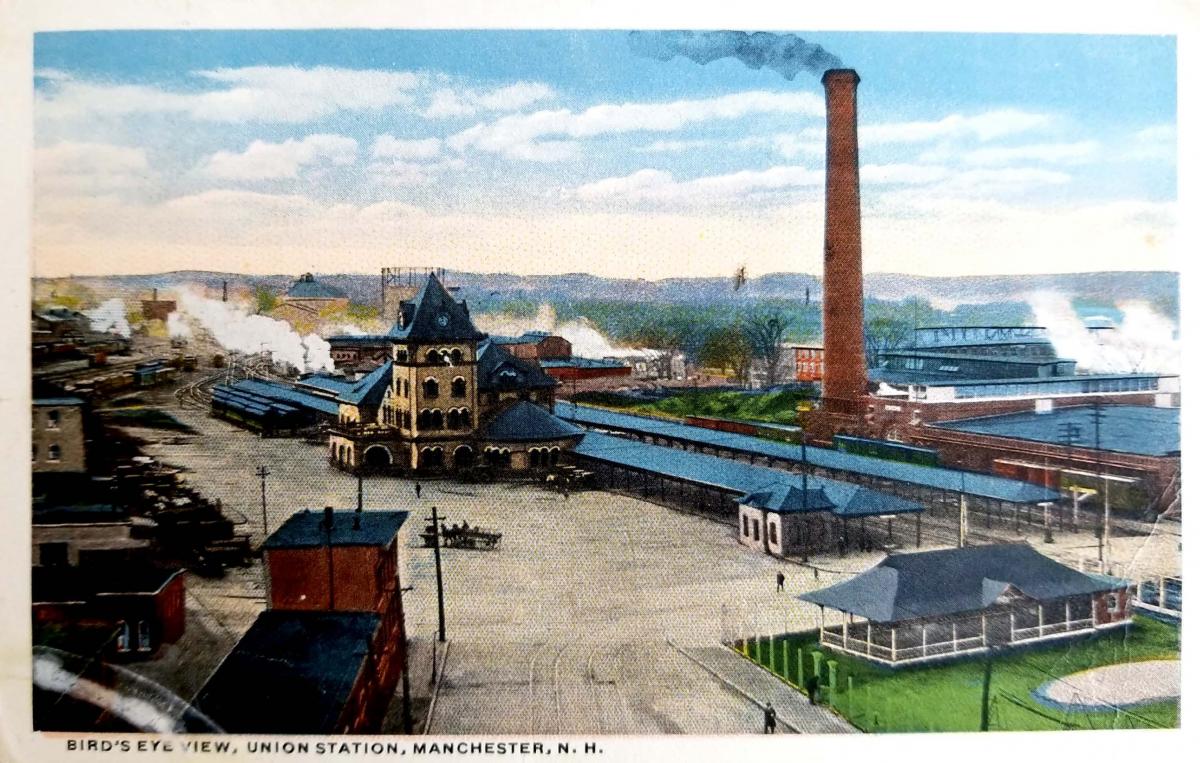

Railroad historians have long overlooked the train station, or looked only at its façade, perhaps in part because railroad archives themselves suggest these narratives. The Hagley Library’s railroad postcard collection offers other views of the station, but these also only depict certain parts. Most of the postcards are views of the main passenger building: the headhouse. They show the façades of these buildings or their immense waiting rooms, but rarely anything more.

The exception to this rule is a pair of views of the Union Station in Manchester, New Hampshire. One shows the station’s sheds over the platforms, the marshaling yards, the powerhouse, and other ancillary buildings. Clearly there is much more to the station than the waiting room or platforms.

Collections like the Reading Railroad archives at Hagley provide further glimpses of stations’ more complicated pasts. The Reading Terminal was not just a place where people went to catch trains, but also one of the country’s first malls in miniature. Philadelphians purchased tickets for trips, bought a magazine at the newsstand or flowers at the florist, and got a haircut or a shoeshine.

The discussions in the railroad’s files about the terminal reveal that people came in off the streets to use the restrooms and the water fountains. In addition to moving through the passenger building, nineteenth century Americans also took advantage of the station’s edges. The poor scavenged coal and conmen lurked outside the station’s doors.

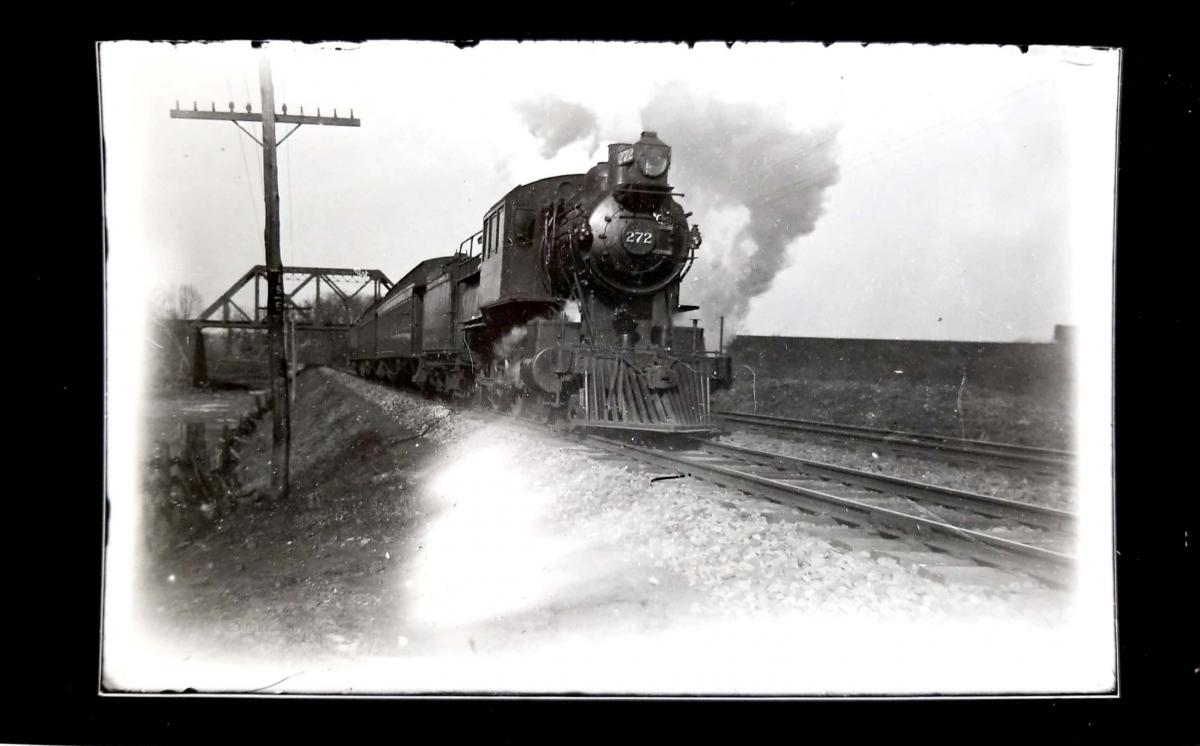

Miles of tracks and powerful locomotives have been subjects for artists, historians, and enthusiasts. My project, made possible with funding from the Hagley and sources from their collections, describes the importance of the large urban train station in nineteenth century American cities.

Zachary Nowak is a doctoral candidate in American Studies at Harvard University. You can listen to an interview with him about his project on our podcast Stories from the Stacks.