Not many people, and not even many music historians, know that the history of magnetic recording technology is virtually coextensive with that of sound recording, dating all the way back to the 1880s. My dissertation in musicology details the story of magnetic tape, and how magnetic recording technology made new kinds of composition possible.

My studies of different kinds of modern music include French composer Pierre Schaeffer’s division of sound from source, which he called “acousmatic listening,” and American composer John Cage’s aggressive radicalism, which resulted in his Music for Magnetic Tape Project collage pieces.

Looking for the beginnings of this technology, I came across Oberlin Smith, founder and president of the Ferracute Machine Company in New Jersey. In 1878, Smith first encountered Thomas Edison’s phonograph. As someone familiar with the principles of metalworking and magnetism, he intuited that translating a sound into electrical current would reduce the phonograph’s mechanical noise.

A decade later, Smith published provisional designs for a magnetic recorder which used steel dust woven into textile thread. That publication would have circulated to none other than Valdemar Poulsen, the Dutch inventor whose 1899 wire recorder was the first patented implementation of the principles of magnetic recording.

But Smith was more than a tinkerer. His philosophical meditations on sound recording helped me see how industrial and manufacturing culture shaped the development of the magnetic media that would become so central to our modern lives. I wanted to understand the worldview and professional life of the first inventor of magnetic recording, so I decided to look into the institutional history of Smith’s business—which is how I ended up on a research grant at Hagley.

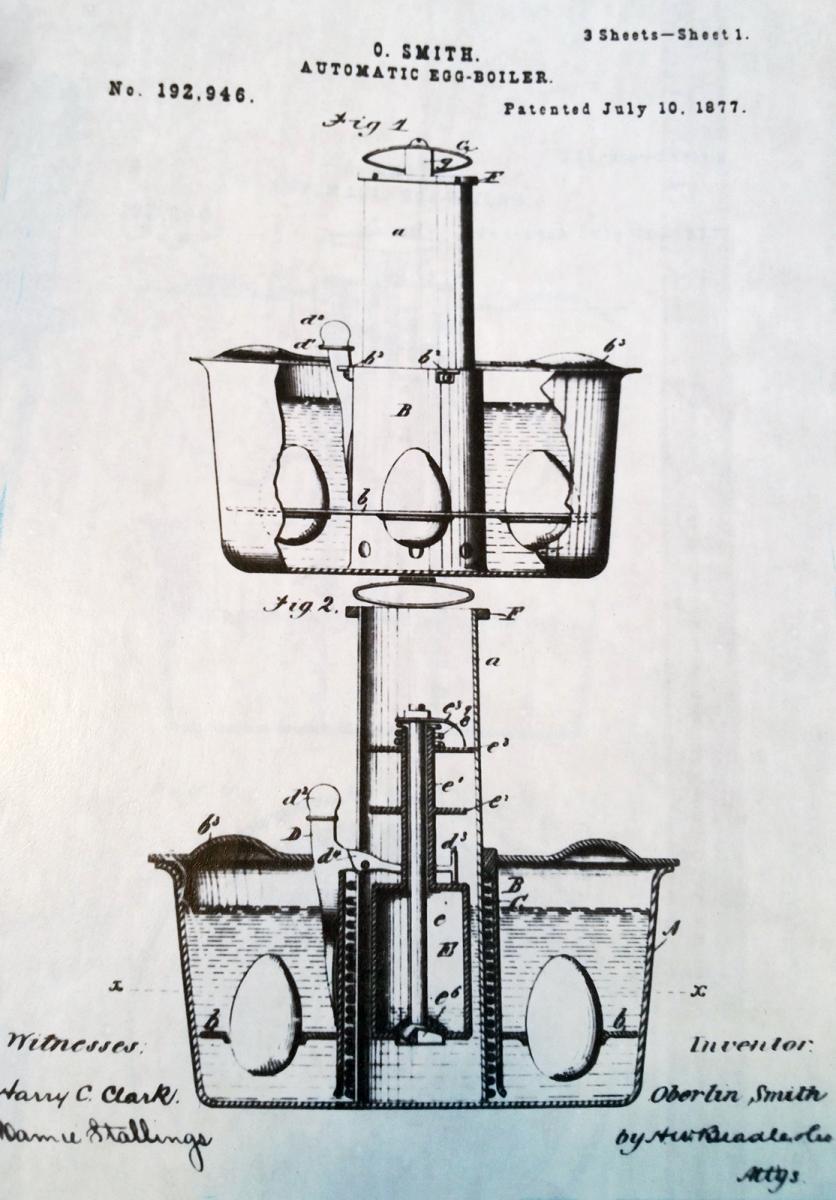

The records of the Ferracute Machine Company gave me better insight into Oberlin Smith’s engineering mentality, an open-minded attitude that would have led to his sound recording design. Among the trade-oriented patent applications for die stamping presses of various sizes and uses, I found some more curious documentation for a machine to boil several eggs at once. Patented within a year of Smith’s idea for a magnetic sound recorder, the Automatic Egg Boiler is an indication of how strong his need for productivity was, even in a simpler design problem such as this.

Although the records at Hagley didn’t contain as much biographical material on Smith as I had hoped, they nevertheless painted a picture of a patrician and captain of industry whose entire life was spent in the development of his business.

Despite his later position as an executive, rather than a hands-on technician or shop floor mechanic, Smith’s engineering mindset kept him thinking about the physical and philosophical possibilities of his thoroughly mechanized work environment. Once Smith witnessed Edison’s phonograph, he immediately began thinking of ways to improve upon it, and his inspiration would go on to echo throughout the development of magnetic recording for the next 70 years.

Joseph Pfender is a Ph.D. candidate in historical musicology at New York University.