Prior to becoming patent model curator, I processed a group of weapons that the St. Andrews School donated to Hagley in 2019. A. Felix du Pont, founder of the school, collected these weapons. They were displayed in custom exhibit cases in the dining hall for many decades.

Two of the handguns in the collection serve as unique examples of how the patent system in America protected the rights of inventors. Further, they demonstrate how this process drove inventors to find creative ways to skirt a competitor’s patent.

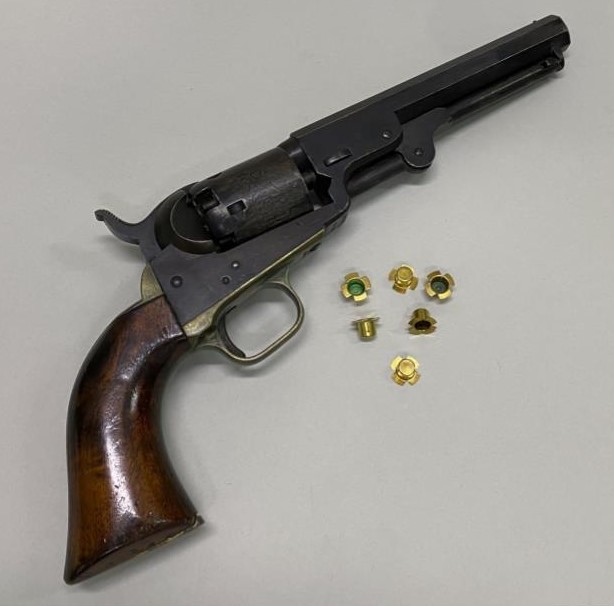

In 1836, Samuel Colt patented his iconic revolver pistol. Among its many unique innovations was that the rotating cylinder containing the pistol loads turned when the pistol was cocked. This saved critical time in a life-or-death situation when every second counted.

Further, Colt included cones on the rear of each cylinder that held a “percussion cap.” Invented decades prior to Colt’s patent, the cap was a great improvement over the unreliable flintlock firing mechanism. These tiny metal caps contained a bit of explosive fulminate of mercury that ignited the gunpowder when the hammer struck the top.

The St. Andrews collection holds three examples of Colt’s revolvers. Here is a photo of one of those pistols with some reproduction percussion caps and a close-up of the cone that would hold them in place.

Colt defended his patents vigorously from manufacturers who imitated or copied his inventions. One of the more persistent pebbles in his shoe was the Massachusetts Arms Company—let’s call them MAC for short. From 1851 to 1852, Colt sued MAC not once but TWICE! The trials were a media sensation and widely followed by an American public fascinated by new inventions. Heated accusations of fabricated evidence and tampering with documents at the Patent Office flew. Colt won both cases—the fact that his attorney was related to the judge probably helped.

MAC was nearly ruined by the loss. Still, they survived to develop strategies for getting around Colt’s patents while still bringing a competitive pistol to the marketplace. Two of MAC’s pistols are in the St. Andrews collection and one is pictured here.

One of the ways MAC got around Colt’s patent was to use a new invention to fire the pistol—the “tape primer.” Patented by Edward Maynard in 1845, it consisted of a sturdy paper roll studded with circular, exploding caps—like those used in our toy guns when we were kids—that ignited the gunpowder when struck with the hammer. The compartment that held the coiled primers, and an original roll, are pictured here.

While there are other features on the MAC that differ from Colt, so as to not violate the Colt patent the cylinder had to be rotated by hand. It wasn’t until 1857, when Colt’s patent expired, that other firearms manufacturers offered pistols that advanced the cylinder by cocking the hammer.

While Colt’s successful defense of his patents scared off many competitors, there were unexpected consequences. His aggressiveness drove them to develop their own improvements. Those represented in the MAC pistol were not very successful, but others were. Soon, Colt lost market share to competitors like Smith & Wesson, Winchester, and many others whose firearms, along with Colt’s, endure as symbols of America and its worldwide dominance in manufacturing and innovation.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library.