The British Army and Navy posed a real threat to Wilmington during the War of 1812. Manufacturers along the Brandywine, such as flour and textile mills and the DuPont powder yards, made enticing targets for an enemy bent on giving “Jonathan” (as the Brits then called Americans) “a good drubbing.”

English military strategists also considered Wilmington a good starting point for an attack on Philadelphia. In the fall of 1777, British forces landed at Elkton, Maryland, marched through Newark, Delaware, won the Battle of Brandywine near Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and went on to capture the American capital at Philadelphia.

Many British senior officers, remembering these successes in the American Revolution, hoped to recreate the tactics that brought them a decisive victory thirty-six years earlier.

Delawareans knew they were in the crosshairs, so to speak. They, too, remembered the British invasion of 1777 and feared the worst. There had also been a steady stream of intelligence that British raiding parties were making their way up the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays with the intention of capturing Wilmington.

Former U.S. Attorney General and Wilmington resident Caesar A. Rodney felt sufficiently alarmed to warn Secretary of the Navy William Jones in March 1813 of the threat. He wrote that “there are objects in this quarter sufficient to entice a British attack,” adding that “the powder mills of Dupont & Co. alone would be thought worthy of destruction.”

E. I. and Victor Marie du Pont acted quickly to protect Wilmington following the British Navy’s bombardment of Lewes, Delaware on 6-7 April 1813. In the weeks leading up to this attack, state authorities mobilized Delaware’s militia companies and sent them to Lewes in order to repel any land invasion. A few weeks later a British naval force sailed into the upper Chesapeake Bay and landed a force of sailors and Royal Marines below Elkton, Maryland.

The du Ponts, realizing Wilmington’s vulnerability, organized two militia companies at their own expense to protect the city and its manufacturers. These companies were called the “Brandywine Rangers” and were comprised of men who worked in the DuPont gunpowder factory and nearby textile mills. Fortunately for Wilmington the British attack on Lewes failed, the Royal Navy moved back down the Chesapeake Bay, and the long feared invasion never materialized.

Wilmington residents’ fears were renewed in late summer of 1814 when the British made another foray into the Chesapeake Bay. Unlike the previous year, the new expedition included more then 5,000 soldiers and nineteen warships.

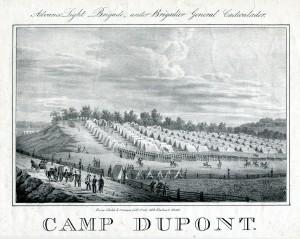

Wilmingtonians understood that the British meant business and began mobilizing all of the forces at their disposal to meet the threat. E. I. and Victor du Pont added a third company to the “Brandywine Rangers” and made sure they had proper arms and equipment. Several militia companies from Philadelphia deployed to Wilmington and created temporary camps at strategic areas, including Camp Brandywine near the DuPont powder yards and Camp Dupont, located close to present day Guyencourt, Delaware.

Revolutionary War hero Allen McLane even organized a militia company called the “Veteran Volunteers,” made up of veterans from the Revolution. The people of Wilmington decided that they would make a determined stand to keep their beloved city out of British hands.

In the end, all of this preparation was not needed. The British forces focused their campaign on the American capital at Washington, D.C., and besieging Baltimore. Following their repulse at Fort McHenry (and providing Francis Scott Key with material for “The Star-Spangled Banner”) the British left Maryland and concentrated their efforts on blockading the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays.

Wilmington, though not attacked, was never out of danger from a British invasion. Had circumstances been different, all of the forces around Wilmington may have had the opportunity to show what DuPont powder would do right in the city where it was made!

Lucas R. Clawson is Reference Archivist in the Manuscripts and Archives Department at Hagley Museum and Library