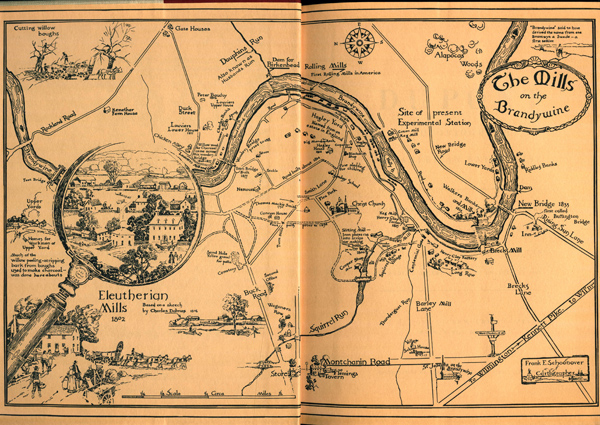

Conventional wisdom holds that one can’t judge a book simply by its cover, it is the content that counts. The next best place to gauge my interest in an illustrated book is an appraisal of its endpapers. Pastedowns and flyleaves are the sheets that attach the body of printed pages known as the text block to the front and back covers of a book. Early bookbinders of the 16th century reached for blank paper or vellum scraps to serve this purpose. But artisans, over time, have employed decorative elements to spark the reader’s imagination, starting in the 17th century with hand-crafted marbleized papers (recently discussed here) and followed by the display of maps.

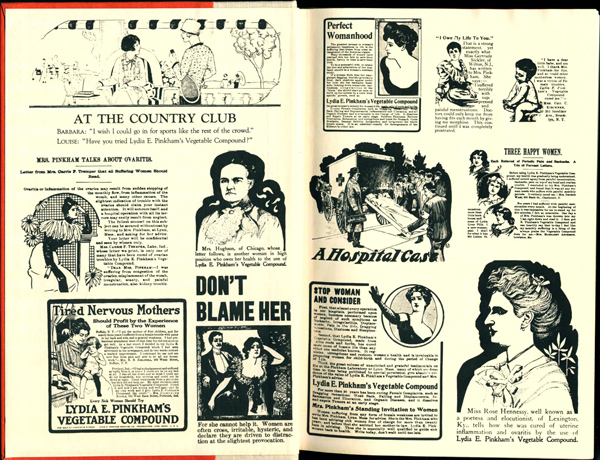

With mechanized printing techniques of the 19th century, endpapers assumed the repeating organic patterns seen in wallpapers. Advertisements found their place here to promote items such as the publisher’s forthcoming imprints.

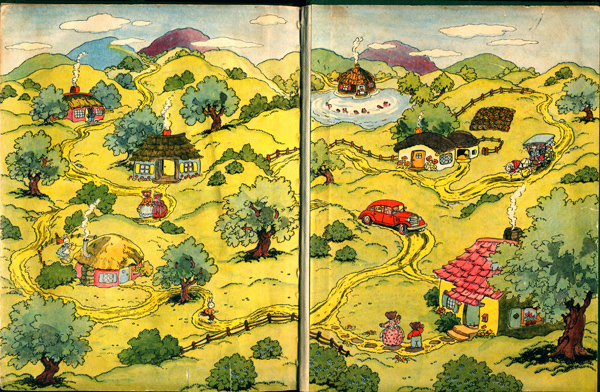

Thanks largely to advancement in 20th-century children’s literature, endpapers have firmly gained a supporting role for text both physically and figuratively by introducing characters, creating mood, setting a theme, and establishing place.

A recent acquisition at Hagley engages the viewer on all of these levels when faced with the opening spread of the volume, Friedrich Engels: das rot-schwarze Chamäleon. In this bicentennial celebration of German political theorist Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), twelve scholarly essays explore the varied contexts of 19th-century industry and society in which Engels emerged as “a red-black chameleon.” Searching to unpack the intriguing title, one finds the color red associated historically with communism and black with anarchism. Political motifs that infused the work of Engels and Karl Marx also course through the palette of Adolph Menzel’s painting, The Iron Rolling Mill.

Menzel succeeded his father as a lithographer in Berlin and achieved high stature as a self-taught painter of large-scale scenes of everyday life. He prepared to create this masterwork by touring and sketching factories in 1872 in his homeland of Königshütte in Silesia (now Chorzów, Poland). Menzel renders with strength and dignity the daily grind familiar to Engels, whose family operated textile mills in Germany and England. Presented as endpapers and supplemented by numerous portraits, facsimiles, plans, and maps throughout the volume, this image primes the reader for a rousing discourse on the industrial revolution in the world of Friedrich Engels.

Alice Hanes is the Technical Services Librarian at Hagley Museum and Library.