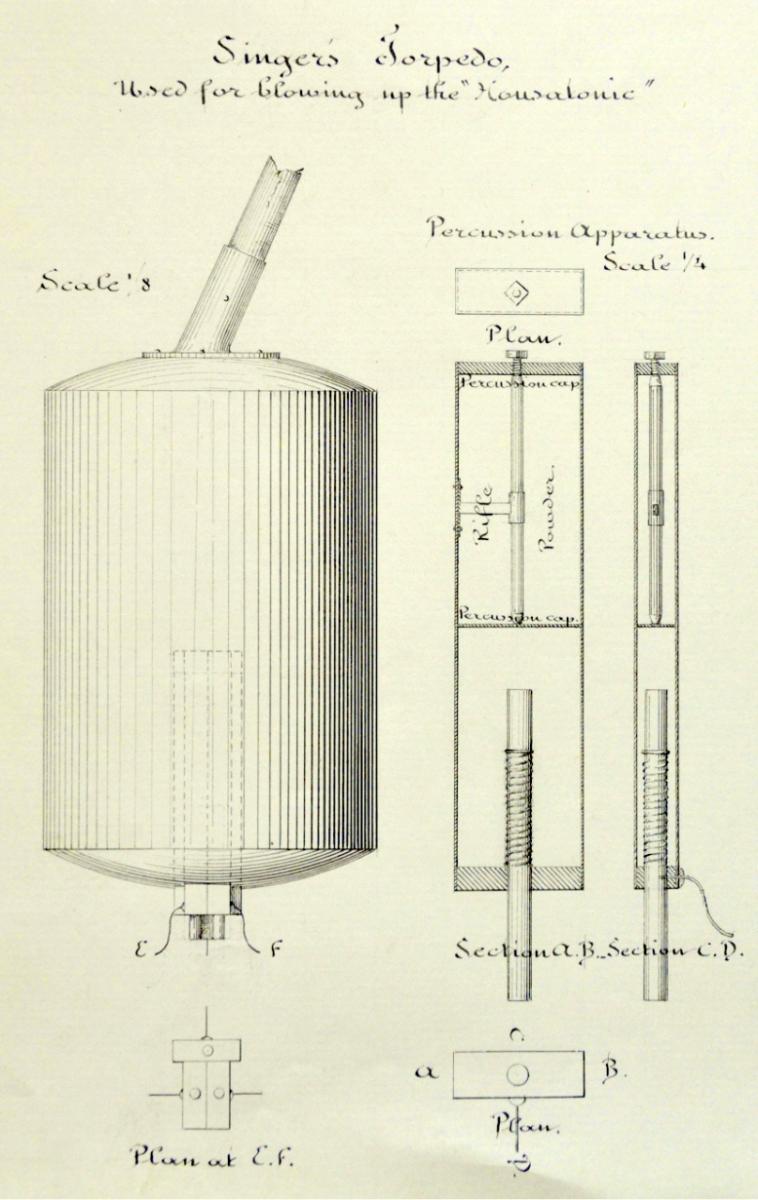

I arrived at the Hagley Museum and Library trying to solve a Civil War mystery. In February of 1864, the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley used a black powder bomb to sink the Union ship USS Housatonic in the waters off Charleston, South Carolina. But in the process, the Hunley sank as well, and all eight men aboard perished. For a century and a half, people had put forth theories about what caused the Hunley to sink, but the reasons remained shrouded in uncertainty.

The mystery of the Hunley’s demise deepened when the sub was raised from Charleston harbor in 2000. The crewmen inside seemed to have died peacefully while still seated at their stations; none showed any signs of skeletal trauma or attempts to escape. The bilge pumps were not set to pump out water, and there was no indication the blast from the charge had damaged the hull in any way.

As a biomedical engineer, I was working to use modern science to figure out what had happened to the Hunley and her crew that fateful night in 1864. I had already evaluated and eliminated the two most popular theories to explain her sinking, and now I was focused on my own favored theory: that the blast propagated inside the hull of the ship and caused lethal trauma to the crew within. To understand if my theory was possible, I needed more information about the black powder used by the Hunley in order to correctly compare it to my modern experiments; but the antiquated nature of the material had stymied my progress. I needed historical data, but wasn’t sure how to get it.

Eventually, after a series of persistent phone calls to the good people who manufacture black powder at Goex, one of their researchers pointed me towards the Hagley Museum and Library. “They have everything,” she said, and then repeated with more emphasis, “everything ever written in America about black powder production.”

She was not wrong.

An exploratory research grant from the Hagley Center provided me the opportunity to make the trip to Delaware and dig in to the archives myself. Over a week in the Library collections and on the Museum grounds, I learned more about the manufacturing of black powder in the 1800's than I had been able to find in months of online literature research. I had the freedom to walk through the old powder mills, to see how they ran, and to talk to the enthusiastic and helpful staff.

I was pretty excited when, after having quietly joined a tour group, the guide asked me directly if I knew what the ingredients for black powder were. Based on his level of surprise, I may have been the first randomly polled visitor to answer that question correctly!

Poring over old documents in the archives, I found a crucial data point that helped me prove my case. Handwritten in ledgers containing the thousands of experiments the du Ponts performed on black powder was one golden data point: using the exact charge weight of the Hunley, during the same time period, and with a pressure measurement. With that pressure measurement, I could compare my modern data to the historical data to show that, yes, the charge was as powerful as I was estimating and had directly led to the deaths of the crew from blast injuries within the hull of the boat without damaging the hull itself.

The historical record helped me interpret my results, and the pieces of the puzzle finally clicked into place.

Rachel Lance received her Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2016, with part of her dissertation focused on the blast trauma experienced by the crew of the submarine H. L. Hunley. She currently works as a research engineer on collaborative projects with Duke University investigating respiratory physiology, and is writing a book on the Hunley and the science required to solve the mystery. You can listen to her discuss her findings at Hagley in an episode of Stories from the Stacks, and follow her on Twitter @UnderwaterLance.