Last month, the Audiovisual Collections & Digital Initiatives Department added a new collection to its digital archive. The new collection, ‘Women's Handicraft in the 19th Century’ includes materials from the library’s holdings that document 19th century American women's participation in household handicrafts, such as cross-stitching, embroidery, knitting, lace-making, millinery, textile crafts, and other domestic arts. It was commonly expected that women of various social classes would take up such crafts as part of their domestic duties, particularly needlework, a skill most of them began training in as young girls.

Women's Handicraft in the 19th Century

Some contemporary feminist critics considered this work to be a frivolous use of women's time and a waste of their intellectual capacity. In Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, for example, Wollstonecraft argued that while men “order their clothes to be made, and have done with the subject; women make their own clothes, necessary or ornamental, and are continually talking about them; and their thoughts follow their hands,” thus limiting the potential of young girls by stifling their minds and instilling an obsession with ornament over matters of importance.

For other women, however, such work provided rare opportunities. Recent scholarship on the topic reveals that household crafts and handiwork could offer outlets for artistic self-expression and personal interests, provided women with opportunities to take part in social and commercial opportunities outside of the home, served as a means of increasing women’s social influence and offered a way to commemorate valued emotional bonds.

Patterns created by the women of the du Pont family devoted their designs to family names and monograms, as well as a large number of hand-drawn floral and other plant form patterns that would have been found in their estates’ celebrated gardens.

Women's handiwork also offered economic opportunity through the creation of personal property with real monetary value. Unlike real estate, which was typically passed through lines of male inheritance, household textiles were legally classified as ‘movables,’ and were handed down from mother to daughter. The value of such goods could be considerable.

In Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth, Ulrich documents the appraisal of the Pynchon family’s estate, finding that, while John Pynchon’s cupboards containing the family’s textiles was valued at three pounds, the bedding and linens within were valued to more than thirteen pounds. Likewise, a single embroidered napkin in his wife’s hand was assessed at three shillings, while most of his land was valued at a rate of four shillings per acre.

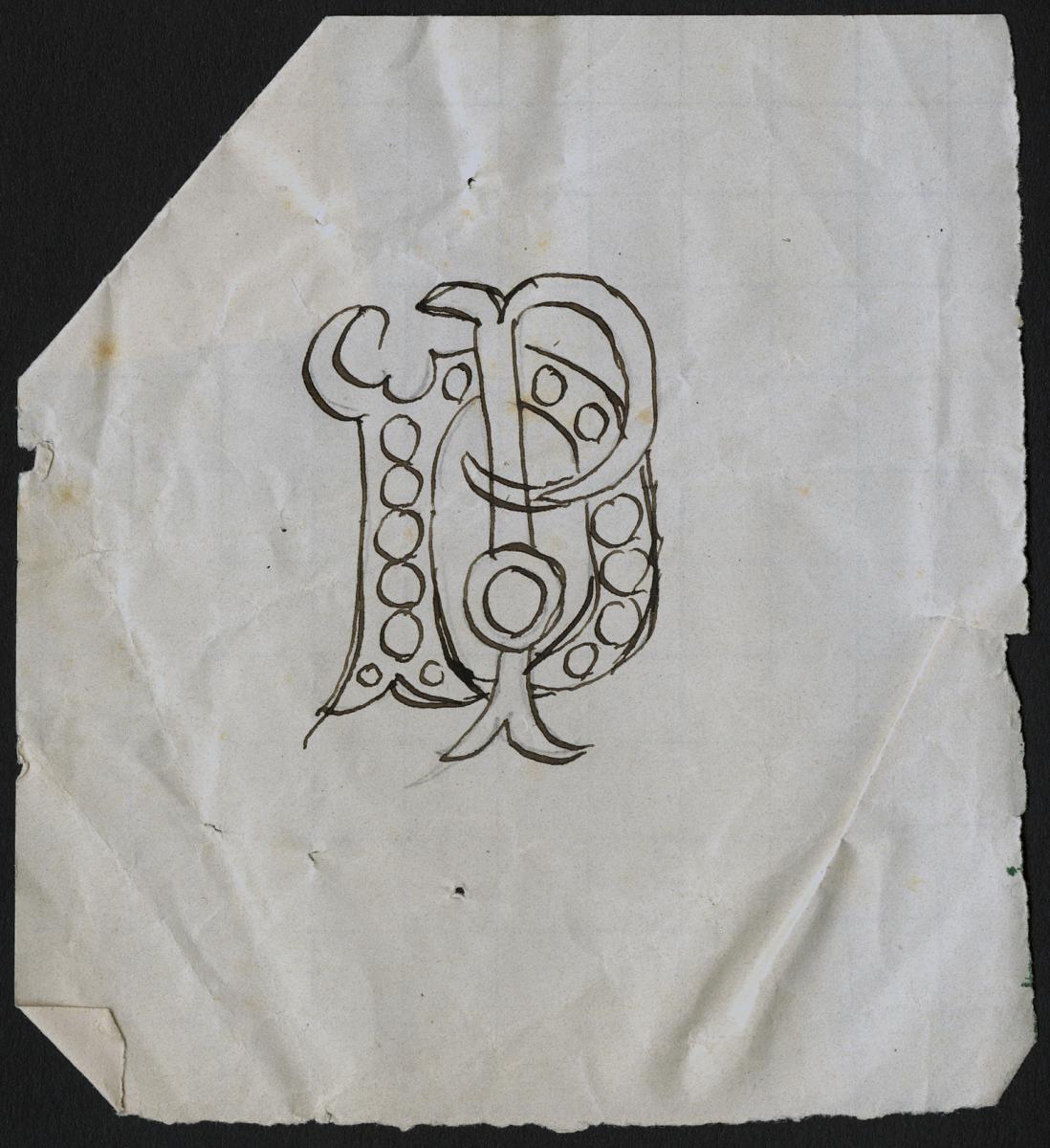

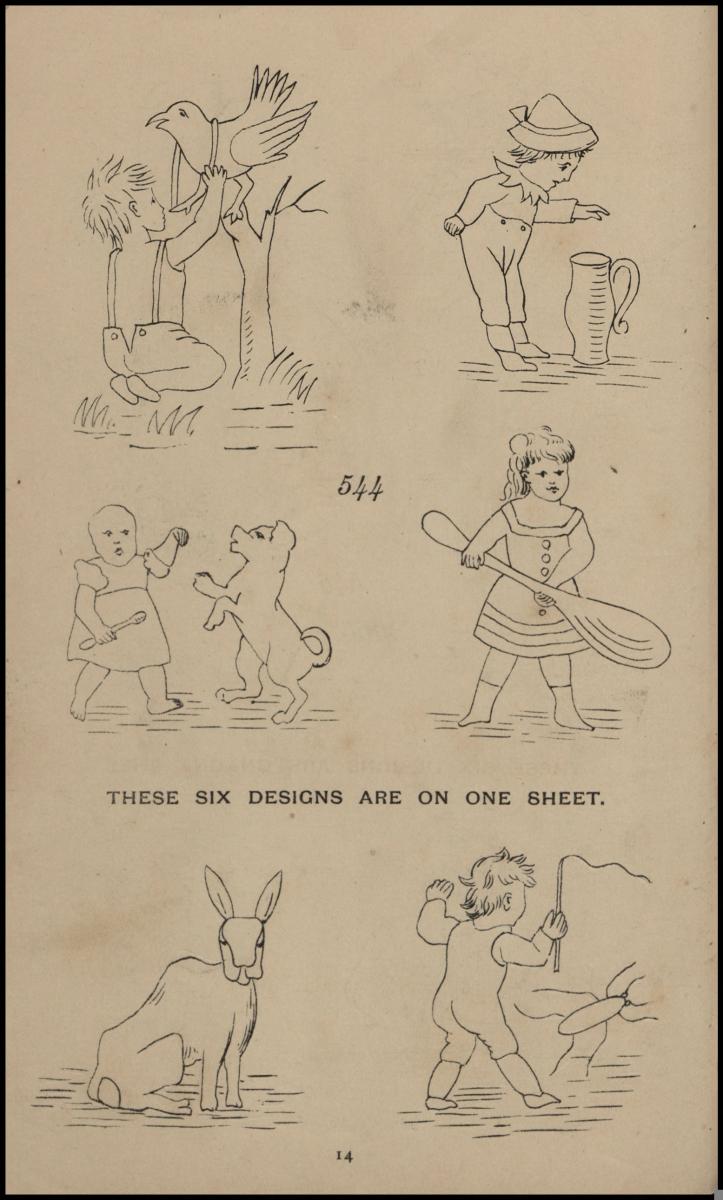

These handicrafts also created an industry to meet the commercial needs of women who wanted to purchase patterns, instructions, and the materials needed to create fancywork and other textile crafts. Within this industry, unique opportunities existed for entrepreneurial women not found in most commercial sectors. Many of the items shown here bear the names of women who leveraged gendered expectations of household handicrafts into occupations as pattern designers, authors, publishers, and embroidery shop owners.

This new online resource offers opportunities for scholars of women’s history, increases the visibility of the du Pont women and women entrepreneurs in the Hagley Library’s digital collections, and may serve a final purpose for those with an interest in women’s handicrafts. Many of the items in this collection were chosen with the generous assistance of the Hagley Museum & Library’s dedicated volunteers in the Handwork Group, who hope to resurrect their use for future projects!

Skylar Harris is the Digitization and Metadata Coordinator at Hagley Museum and Library.