In May 2025, Canada completed the first year of a planned 25-year, one-billion-dollar restoration project for the Quebec Bridge. This famous bridge is the longest cantilever truss span in the world, stretching 1,800 feet (549 meters) between its supports and 3,239 feet (987 meters) in total. Finished in 1917, it unfortunately stands as proof of the adage, “third time’s the charm.”

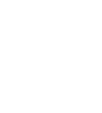

Discussions about a bridge over the lower Saint Lawrence River, connecting Sainte-Foy and Lévis in Quebec, began in the early 1880s, but serious planning started in 1900. The planned bridge would measure 2,800 feet (about 853.44 meters) long and rise over 150 feet above the water to allow ships to pass beneath. It was to be at least 67 feet (20 meters) wide to accommodate two railway tracks, two streetcar tracks, two vehicle lanes, and pedestrian access. The Quebec Bridge & Railway Company, with support from local and federal governments, hired the renowned American engineer, Theodore Cooper, to lead the project.

Discussions about a bridge over the lower Saint Lawrence River, connecting Sainte-Foy and Lévis in Quebec, began in the early 1880s, but serious planning started in 1900. The planned bridge would measure 2,800 feet (about 853.44 meters) long and rise over 150 feet above the water to allow ships to pass beneath. It was to be at least 67 feet (20 meters) wide to accommodate two railway tracks, two streetcar tracks, two vehicle lanes, and pedestrian access. The Quebec Bridge & Railway Company, with support from local and federal governments, hired the renowned American engineer, Theodore Cooper, to lead the project.

The Phoenix Iron Company in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, developed the technology needed for this project. They created the Phoenix Column—patented by Samuel Reeves in 1862—a hollow cylinder made of four, six, or eight iron segments riveted together. Such a design was lighter and stronger than traditional solid cast iron columns, allowing for the construction of large structures without needing massive support walls. This advancement enabled the construction of skyscrapers and high-stress, load-bearing bridges, like the one required to cross the Saint Lawrence. These columns and their in-house engineers made the company’s subsidiary, the Phoenix Bridge Company, an industry leader and specialist in cantilever bridges.

It is no surprise that Phoenix's proposed design was selected over the competition. According to Cooper, Phoenix engineers Peter Szlapka and J. Sterling Deans submitted a plan that was "exceedingly creditable in terms of its overall proportions, outlines, and constructive features," making it the "best and cheapest" option among those submitted.

And that is when it all started to go wrong.

For most of the 19th century, bridge companies handled all parts of projects themselves, including design and manufacturing. By 1900, this method had become outdated. Plans were typically reviewed and approved by other engineers before being sent to a bridge company for manufacturing. Therefore, it was a strange move for Cooper to select Phoenix to also make the components they designed.

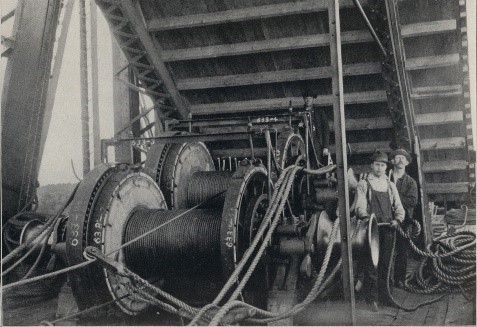

Unfortunately, that was not the only questionable decision Cooper made. Although he was hired to oversee the project, he worked from New York due to “health issues.” Construction of the bridge began in 1905, shortly after Szlapka submitted the initial drawings. The weight estimates for the bridge were based on these drawings.

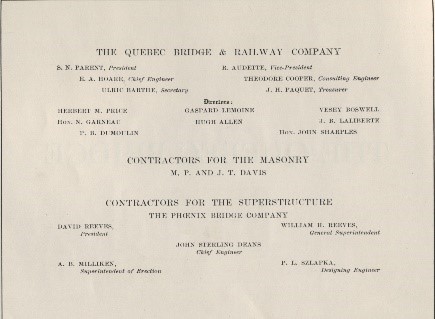

It was seven months after the first girder was placed (see right) and the southern half of the bridge neared completion that Cooper saw the working drawings and noticed the mistake. In cantilever bridge design, achieving the correct balance of weight in the center span is the most critical factor; the bridge currently under construction was eight million pounds off from the original estimates. Instead of halting construction and beginning again, Cooper determined that eight million pounds was within engineering tolerances. His decision was likely shaped by the upcoming inauguration of the marvel by the future king of England in 1908.

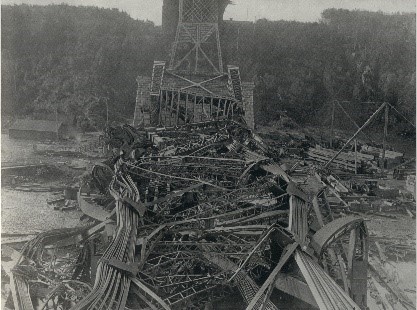

On June 15, 1907, an inspecting engineer observed that two girders were misaligned. Two months later, the girders had shifted a few more inches and developed a noticeable bend. The inspection team then decided to bring their findings to Cooper's attention. To avoid alarming the public by using the party line phone, they sent a representative to meet with him in person in New York. Construction continued. Unfortunately, as the meeting was ending on August 29, the bridge collapsed, killing 75 workers. Despite the second attempt by the St. Lawrence Bridge Company collapsing due to flaws in the construction equipment, the first Quebec Bridge has served as a cautionary tale for bridge engineers for over a century.

Since the early 1970s, Hagley Library has maintained the records of the Phoenix Bridge, which is part of the Phoenix Steel Corporation collection. This collection includes documents related to the design and planning of the Quebec Bridge, the internal investigation, and the coroner's reports following the disaster. A detailed finding aid on the Phoenix Steel Corporation, including Phoenix Bridge records, is now available online for researchers. Additionally, you can find photographs of the bridge's construction in Hagley's Digital Archives. However, to view the over two hundred working drawings and plans from the Phoenix Bridge Company, you must visit our site in person—don't make the same mistake as Cooper!

Sharon Folkenroth Hess is the Library Specialist at Hagley Museum and Library