In 1957, there was sudden excitement and praise in the art world over a novel method of artmaking developed in France in the ‘20s. A retrospective of 50 works by Pablo Picasso (see right) was being held in Paris. This exhibit was distinct in that the works on display were made by a recently invented process known as gemmaux (pl.) or gemmail (sing.).

Developed by Roland Malherbe and his son Roger, gemmaux uses pieces of glass arranged on a glass plate to create an image. These glass shards can be layered to create depth of tone or color. When the composition is finalized, it is covered by a clear enamel, then baked in an oven to seal it. Backlit in a window or illuminated via light fixtures, the gemmaux works have a dazzling luminosity, more open and ethereal than the hard lines of stained glass.

At the time there was a great deal of hype around gemmaux. Picasso, in a publicized occasion, wrote on a card his endorsement of the medium, hailing it as a “new art.” The latter’s partner in Cubism, George Braque, declared that “If I were thirty years old, I would be the ‘Gemmist Braque.’” Jean Cocteau, the poet and filmmaker, was so won over by these new works that he even became president of the Judges of the Prix du Gemmail.

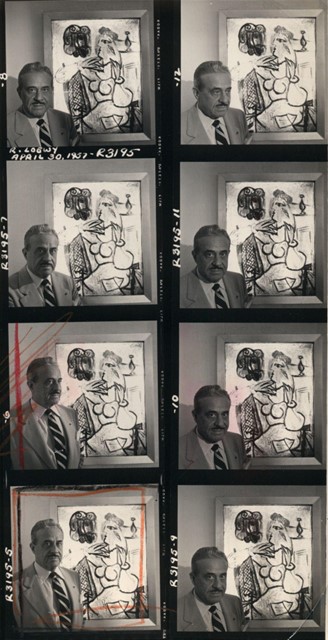

While this was going on, industrial design legend Raymond Loewy became interested in gemmaux and invested in two pieces; one a transcription of a Gaugin, the other a Picasso (see right). The latter was appraised and made a posthumous gift to the Evansville Museum of Arts, History & Science in Indiana.

While this was going on, industrial design legend Raymond Loewy became interested in gemmaux and invested in two pieces; one a transcription of a Gaugin, the other a Picasso (see right). The latter was appraised and made a posthumous gift to the Evansville Museum of Arts, History & Science in Indiana.

Ask most people today if they know what gemmaux is and you’re not likely to get many affirmative answers. The fervor for gemmaux seemed to die out quickly, despite several exhibits and high-profile endorsements. Creating the pieces was time consuming and required a team of “gemmists” just to create one piece. These complexities may have been too much for the art form to be a practical medium for artists to attempt very often. Nevertheless, it is an unexpected and fascinating corner of art history and existing examples of gemmaux itself are beautiful.

The documentation regarding Raymond Loewy’s gemmaux pieces, as well as related photos and press materials, may be found in the Raymond Loewy archive (Acc. 2251, Box 2) here at the Hagley Library. This includes all the images from this article. To access the materials, please reach out to Reference Services at askhagley@hagley.org.

Alex Lattanzi is the Collections Assistant at Hagley Museum and Library