This is one of those happenstance occurrences that so pleases funders. I was at Hagley in the summer of 2010 to read through late nineteenth century papers on food and agriculture. I’m in the middle of a project about food, purity, and nature in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. I’m drawn to debates about authenticity and purity—in the public sphere in general, but specifically with reference to new artificial foods—before Pure Food legislation of the early 1900s. I had a laundry list of sources to consult. I had my camera ready for snapshots.

This is one of those happenstance occurrences that so pleases funders. I was at Hagley in the summer of 2010 to read through late nineteenth century papers on food and agriculture. I’m in the middle of a project about food, purity, and nature in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. I’m drawn to debates about authenticity and purity—in the public sphere in general, but specifically with reference to new artificial foods—before Pure Food legislation of the early 1900s. I had a laundry list of sources to consult. I had my camera ready for snapshots.

Then I found out the free range offered funded researchers that I could wander the stacks unfettered. I was making my way down an aisle to grab Philadelphia Market Reports from 1872 when a long run of old-ish looking journals caught my attention. They were at eye level. The spines said The Spice Mill. I never heard of it and was not really interested in spices. I certainly didn’t write my grant application with The Spice Mill in mind.

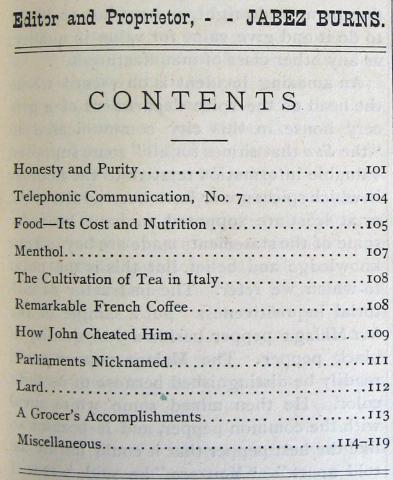

But…. it turns out The Spice Mill, edited in New York by “Machinist, Inventor, Manufacturer, and Dealer in all kinds of Coffee and Spice Mill Machinery” Jabez Burns, is a marvel of late-century documentation about purity and adulteration. Burns was also a fairly prolific inventor, with his name on handfuls of patents dealing with machines, coffee grinders, and other apparatus of the coffee trade. I found this out after pausing in the aisle, grabbing a few volumes, and sitting down right there to leaf through them. It turns out Burns called the “paper the SPICE MILL, because we intend to deal in a spicy way with the spice of active manufacturing business life.” Beginning as a quarterly, The Spice Mill became a monthly periodical by its third volume; Hagley has a complete run through 1919.

But…. it turns out The Spice Mill, edited in New York by “Machinist, Inventor, Manufacturer, and Dealer in all kinds of Coffee and Spice Mill Machinery” Jabez Burns, is a marvel of late-century documentation about purity and adulteration. Burns was also a fairly prolific inventor, with his name on handfuls of patents dealing with machines, coffee grinders, and other apparatus of the coffee trade. I found this out after pausing in the aisle, grabbing a few volumes, and sitting down right there to leaf through them. It turns out Burns called the “paper the SPICE MILL, because we intend to deal in a spicy way with the spice of active manufacturing business life.” Beginning as a quarterly, The Spice Mill became a monthly periodical by its third volume; Hagley has a complete run through 1919.

I honestly had no idea the journal would be so useful for me. A few secondary histories of coffee refer to The Spice Mill as the first American paper devoted to coffee and spices and Burns as a purveyor of those coffees and spices and assorted other grocery items. But even in the first issue (January 1878) Burns deals with adulteration, artificial foods, frauds, tricks, trust, and honesty, with several articles on what the New York Herald called the “War on Oleomargarine.”

In the other volumes I read through in my time at the Library, The Spice Mill dealt with adulterated confectionery, adulterated bread, adulterated olive oil, butter versus margarine, adulteration and cottonseed oil; it discussed journalistic adulterations, a number of pieces on “the adulteration of food” in general, a bill on adulteration in congress, “Terrific Adulteration in France,” new British regulations on coffee and chicory and against adulteration; and it addressed the art of adulteration, new methods of adulteration, The Age of Adulteration, and a four-part series called simply “Honesty and Purity.”

In the other volumes I read through in my time at the Library, The Spice Mill dealt with adulterated confectionery, adulterated bread, adulterated olive oil, butter versus margarine, adulteration and cottonseed oil; it discussed journalistic adulterations, a number of pieces on “the adulteration of food” in general, a bill on adulteration in congress, “Terrific Adulteration in France,” new British regulations on coffee and chicory and against adulteration; and it addressed the art of adulteration, new methods of adulteration, The Age of Adulteration, and a four-part series called simply “Honesty and Purity.”

And then there was more: Burns apparently had some strong views about women and the potential for women’s rights (not always a fan, was he). He also had an unexplained fascination with reporting news about Jewish traders and Jews in America.

Clearly, Burns was after far more than commentary on coffee and spices -- just as I, in my hoped-for research, was after more than straightforward tales of adulteration.