As I write this, local retailers are shifting their displays from Halloween to the holiday season. Lights, trees, and brightly wrapped packages are replacing ghosts and goblins. Leaf-strewn lawns and sagging jack-o’-lanterns are now covered in a thin layer of frost as consumer culture marches into the next season.

Seasons may change and influence our retail experience, but the American desire for the next gizmo or doodad is evergreen. As industrialization revolutionized nearly every aspect of American life, 19th-century consumers took a similar attitude towards machines that we now have towards the internet and computers. Much like we add apps and other chips and software to the products on holiday store shelves, Americans during the golden age of invention believed that anything and everything could be improved if they applied some mechanical solution to an ordinary product. This extended to that class of products that are always present in the holiday memories of our youth: TOYS!

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most playthings were made at home or improvised with whatever materials were available. Members of the wealthier merchant class purchased imported European toys made by craftsmen. But that was a small percentage of the playthings enjoyed by American children.

By the mid-1800s, American factories were mass-producing toys, which made them more affordable. Steam power reduced labor needs and die-cast or molded parts created standardization and interchangeability that further lowered costs. New, inexpensive, durable, and moldable materials such as tin, steel, and iron changed common toy composition. Though bright, hand-painted accents continued to be applied to the toys, advances in mechanization allowed manufacturers to add bold, printed papers that enhanced the objects’ appearance.

The introduction of motive power through clockwork mechanisms further changed toys and how children interacted with them. Children and adults alike were drawn towards mechanized toys that walked or moved. Hagley owns a patent model for a toy that used this new fascination with motive power in a unique way.

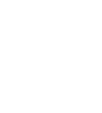

This model for a wooden toy fish has a thin, metal tail cut to resemble that of a real fish. It is connected to an interior clockwork mechanism that moved it from side to side. The inventor, Robert Hunter (1823-1899), claimed that it “gave the appearance of life when placed in the water, and cause[d] it to swim with precisely the same motions of a live fish.”

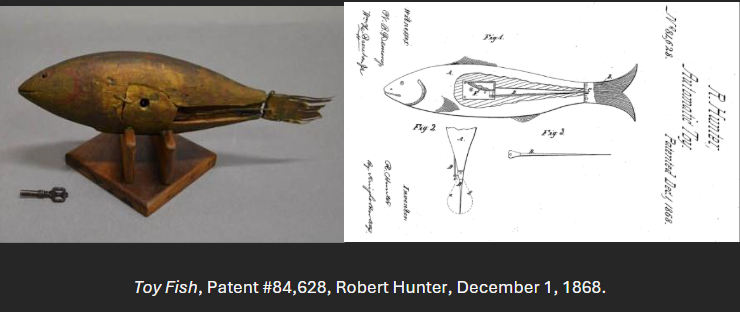

He also claimed that it could be used on toy boats. And it is in that arena that he most applied his creative and inventive energies. Inspired by a prize of $100,000 offered by the state of New York for the best method of using steam power to replace animals for towing canal boats, Hunter earned seven patents for boat propellor designs—including one that closely resembles a fish tail (see below). His designs worked well but were judged to be too complicated for the average canal pilot to operate and likely to suffer mechanical failure that would require lengthy and costly repairs.

But Hunter’s inventive talents were not his most notable accomplishments. He studied medicine at New York University, graduating in 1846. Hunter specialized in respiratory diseases and, upon graduation, furthered his education by studying in Europe. He practiced medicine in London, Toronto, New York City, St. Louis, St. Paul, and Cincinnati. Patients likely appreciated his medical genius over his mechanical one.

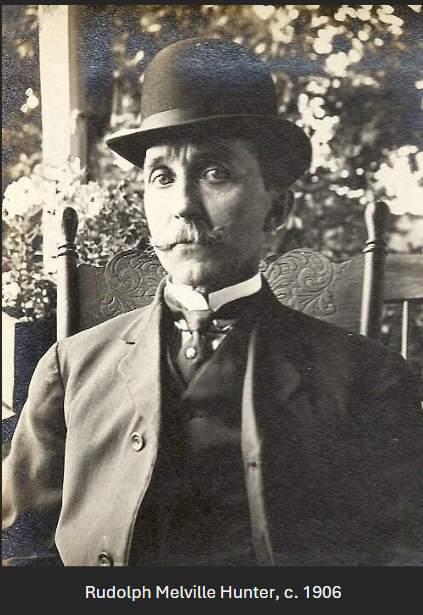

Hunter inspired his son, Rudolph Melville Hunter (1856-1935), to start inventing at a very young age. The younger Hunter would go on to earn over 300 patents. His inventions related to the operation of electric railways were acquired by General Electric and helped that company become a household name. Rudolph later dedicated himself to alchemy, seeking to change silver into gold. Though he claimed success and many prominent citizens vowed for his character, stating that he was no swindler or charlatan, his results could not be replicated.

Be sure to visit this patent model this holiday season near the entrance to Nation of Inventors, Hagley’s permanent exhibition celebrating American invention and innovation and featuring over 100 patent models.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library