As I write this, I am only one week into the New Year and still upholding my resolution to participate in “Dry January.” Non-alcoholic drinks such as flavored seltzers and sodas replace my usual nightcap of wine or whiskey. This inspired me to write about a patent model in our collection designed to help soda mixologists prepare similar alcohol-free concoctions. It was invented by John Matthews Jr. whose father was called the “Soda Fountain King” of New York City.

Beginning in colonial times, Americans traveled to natural mineral and hot springs to drink or bathe in the waters. Since they believed that they offered health benefits and relieved symptoms from illnesses, they were imported and dispensed at pharmacies. To improve the taste, they were sometimes mixed with concentrated fruit syrups, herbs, spices and alcohol.

In January 2023, I highlighted one of the early entrepreneurs in the soda business, Eugene Roussel (1810–1878). He imported waters from nearby natural springs and began selling them in Philadelphia around 1839. But he built his business around naturally carbonated beverages.

John Matthews (1808–1870), on the other hand, cut Mother Nature out of the process and began artificially adding carbonation to water starting seven years earlier in 1832. Born in England, Matthews immigrated to New York City that same year. As a teenager, he apprenticed with prolific English inventor Joseph Bramah (1748–1814), and it is perhaps in Bramah’s shops that he learned to manufacture carbon dioxide gas.

Previous formulas involved adding some form of calcium such as chalk to an acid. His technique involved adding marble dust to sulfuric acid. The resulting gas was collected, purified by passing it through water, rocked in a tank to trap the bubbles in the liquid, and finally salts were added to imitate the flavor of natural mineral waters.

Why marble dust? There was a cheap and near limitless supply. New York City was booming and marble was used in the construction of many new buildings. Matthews visited the worksites and collected scrap pieces discarded by sculptors and stonemasons. One of his preferred stops was the future site of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Since it took nearly three decades to complete, and included many carved marble elements, it could have supplied him for many years.

His business thrived thanks in no small part to the Temperance movement. Increasing numbers of Americans pledged to “totally” never touch alcohol again—thereby becoming “T-totalers”. His sodas, in addition to the equipment he manufactured for dispensing them, were so popular that he owned over 500 dispensaries in the city alone. This earned him the nicknames the “Neptune of His Trade” and the “Soda Fountain King.”

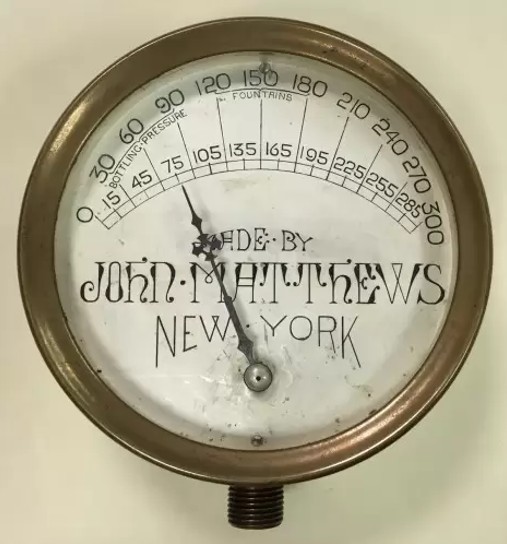

His son, John Matthews Jr. (1832–1883), was important to the growth of his business. A machinist by training, he patented many inventions that helped make the manufacturing, dispensing, and transport process safer and more efficient. His first patent in 1855 (#13,468) was for a pressure gauge. Here is one of his later versions:

This device was critical for impregnating the water with the gas. The pressure had to be in the correct range so that there was plenty of fizz. But too much pressure could cause an explosion.

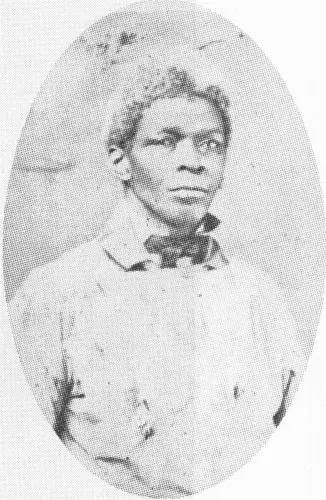

There was one highly valued employee of the company who probably scoffed at such a gadget. Pictured below, Ben Austen operated a pushcart selling the Matthews’ sodas on the streets of New York City. His technique was to hold his thumb over the pressure outlet. When the pressure got to be too strong for him to keep his thumb in place, it was just right. This ideal pressure range was known as “Ben’s Thumb” and became a carbonated beverage industry catch phrase.

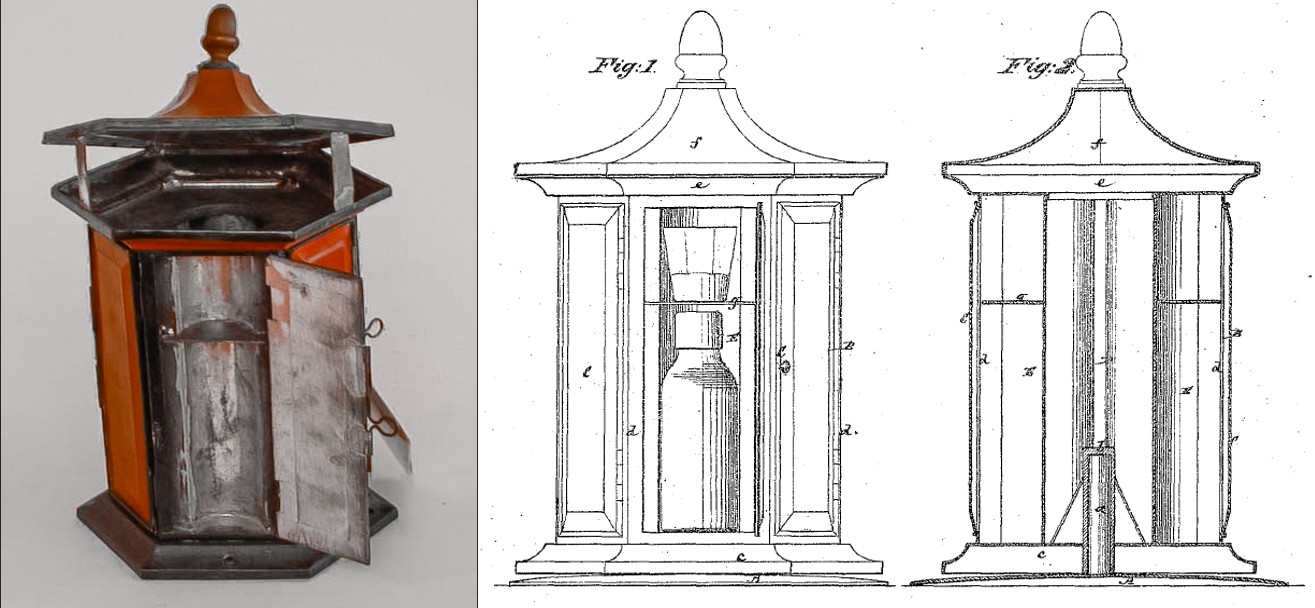

John Matthews Jr. received over 70 patents for inventions related to the industry ranging from gas generators to wagon designs for transporting soda fountains. Despite his output, only one of his patent models appears to have survived. It is in Hagley’s collection and is pictured below.

Improvement in Refrigerators, John Matthews, Jr., New York, NY, August 15, 1871

Improvement in Refrigerators, John Matthews, Jr., New York, NY, August 15, 1871

This invention is a refrigerated cabinet for chilling flavored syrups and glass tumblers. It has six compartments, each with a door and two shelves—one for holding the tall, cylindrical syrup containers on the bottom and another shelf for the tumblers on top. The domed lid opens for filling the inner chamber with ice. It rests on a base that spins so that the user can quickly access a fresh glass or whatever flavor a customer desired.

A few months prior to this patent, John Matthews Sr. died. He was interred in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, the premier permanent address for rich and famous deceased New Yorkers. His monument, one of the most spectacular in the entire cemetery, is pictured below and reportedly cost $30,000 to build (over $700,000 in today’s dollars). Acid rain has weathered and softened the marble carvings over the past 150 years. Fittingly, this is the same chemical reaction of acid plus marble that enabled him to build his soda empire and afford this grandiose monument.

While the decoration alone is stunning, it does have one very unique feature. During rainstorms, water gushes from the mouths of the gargoyles perched on the roof. It’s not carbonated, but I get the connection to the family business.

John Matthews Jr. soon joined his father in Green-Wood. He died at age 52 in 1883. He died unexpectedly of kidney disease and was still working on new inventions at the time. Five were patented in his name posthumously.

So when you crack that bottle of flavored seltzer or pop open a can of soda, take a moment to think of the inventors who helped make this fizzy, thirst-quenching treat possible. At least, until the first of February.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library