According to an AI search, up to 15% of humans have a fear of spiders. Strangely though, spiders get a pass during the build up to Halloween. Spider-themed decorations adorn many homes and businesses with nary a blink or shudder from passersby. With that in mind as the holiday approaches, I hope, dear reader, that you can put aside your fears for once and show a little pity for the poor spider as I am about to introduce you to a one-of-kind patent model that tortured spiders in a quest to create a new textile industry for formerly enslaved Americans.

The silk industry has relied on the silkworm for centuries. But wily naturalists recognized that there are other animals that produce silk, including spiders. Spider web silk is unique, and in many ways superior to that of the silkworm. Spiders produce multiple types of silk each having different purposes as well as different properties—from anchoring and forming the framework for their webs to catching and enveloping prey. Their silk is composed of long strands conducive to weaving, stronger than steel, and highly conductive. Plus, spiders can make an awful lot of it!

For hundreds of years, these facts inspired many attempts at making spider silk cultivation a successful industry. Trouble is that spiders are less cooperative in captivity than silkworms. They require lots of space to weave their webs, demand great quantities of living food, and are so territorial that if you put a bunch of spiders in a single container, soon all you will have left is one big fat spider! This made the spider a less-than-ideal candidate for silk production on an industrial scale. That didn’t stop folks from trying—and Hagley has the patent model to prove it.

During the campaign to capture the city of Charleston, South Carolina during the American Civil War, two Union officers of the 55th Massachusetts—a regiment composed of Black soldiers led by White officers—were stationed on nearby Folly Island. The unit was formed at the same time as the 54th Massachusetts, which was the subject of the 1989 movie Glory. One officer was a surgeon named Burt Wilder who, in addition to studying medicine, also was a budding naturalist. The other, Sigourney Wales, was the regiment’s major. They, like other soldiers in the regiment, stumbled into massive, golden spider webs strung between trees around the island, some up to six feet in diameter. These webs were made by a species now named Triconophilia Nevipes, more commonly known as the golden orb weaver. They are one of the largest non-tarantula species of spider in North America.

But they, like tarantulas, are also very tame. The officers obtained live specimens of the spiders and kept them in cigar boxes in their tents. And, being twenty-year-old men with too much downtime, they naturally began using them for entertainment. Wilder pinched a bit of the spider’s silk from its backside and began pulling. Normally spiders will use their back legs to snip off the silk when this is done. But that didn’t happen. So, naturally, he just kept pulling. Soon he had a strand six feet long of web silk. He kept pulling, until, as he later claimed, he was able to pull 250 yards of golden silk from a single spider!

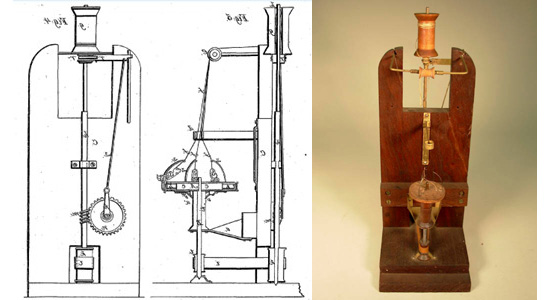

Wilder then salvaged a few spare bits of metal and wood and rigged up a machine to pull the silk and wind it around a spool. Wales, from a family of furniture makers, used the skills he learned in his father’s workshop to carve some wooden trinkets, such as rings and Christian crosses. They used Wilder’s machine to wind the golden silk around the trinkets and sold them to their fellow soldiers and local civilians. Later, the men claimed that the silk was so brilliant the objects were mistaken for real gold.

After the war ended, Wilder and Wales did not forget this experience. They recognized that now that slavery was abolished, agricultural products were needed to replace crops like cotton and rice that were only profitable through enslaved labor. What if cultivation of silk from the spiders that infested Folly Island, and the surrounding Carolina coast, could be one of those alternatives? Still, if they were going to make this work, the pair would need a better silk harvesting machine than the one Wilder cobbled together from scrounged parts. The result was this patent model—the only known surviving model for this purpose, and perhaps the only American patent awarded for extracting silk from live spiders.

The design they came up with involved attaching up to five spiders on a revolving turntable—or the “spider-fuge!” They used rubber bands to secure the gathered legs of the animals to the turntable with their backsides, full of the spinnerets that produced the silk, pointing upward. The silk was then drawn from the spider upward, fed through some curved metal guides, and on to a spool. A series of gears rotated the turntable, thereby spinning the silk into thread, and wound it on the spool. The revolutions per minute were not stated in the patent specifications, but to obtain enough thread to weave a garment, these spiders would have been subjected to hundreds of rotations per session. Poor dizzy gals! Yes, they would have been females. Like most spider species, the females are much larger than the males and weave the webs to catch prey.

With patent in hand, Wilder and Wales now needed to promote their invention and attract investors. The promotion part was easy! Newspapers all over the United States east of the Mississippi reported on their discovery. The men imported one of the spiders to Boston, Massachusetts and set it up in a store window where curious onlookers could watch the spider construct its web. They recognized that they needed to expand their capacity to make this venture profitable, so the duo devised another machine that used 64 spiders!

Sad for them, but good for the spiders, Wilder and Wales’s scheme was viewed more as a novelty than a potentially profitable industry. The machine was soon forgotten and the inventors got on with the rest of their lives’ work.

Wilder earned a medical degree from Harvard. He specialized in studying the anatomy of the human brain and is credited with codifying the naming of brain cells such as neurons, a process called “neuronomy.” Ironically, in 2016 scientists studying neurons found that one of the substances that could restore signals between severed neurons was—you guessed it—golden orb weaver spider silk!

One of my other inquiries when studying this machine was: “Is that golden thread on the spool and the metal guides actual spider silk?” If the inventors were collecting hundreds of yards of the stuff, wouldn’t they want to wind it on their machine to impress the patent examiners? That’s another mystery, and another story, for another time—perhaps next Halloween! In the meantime, even if you are afraid of spiders, pity the poor golden orb weavers who had to endure a very dizzying existence due to the efforts of two very well-intentioned inventors on a quest to provide a profitable industry for newly freed enslaved Americans.

Be sure to visit this patent model this fall near the entrance to Nation of Inventors, Hagley’s permanent exhibit celebrating American invention and innovation featuring over one hundred patent models.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library