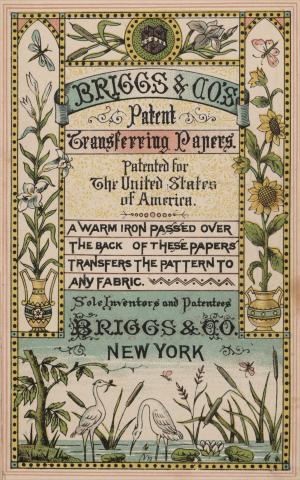

Brr! December means indoor kid weather, so here’s a #ThursDIY post for all you cozy crafters. This illustration accompanied a ca. 1880s catalog of Briggs & Co.’s patented embroidery patterns.

Briggs & Co. was founded in 1874 by John Briggs, who patented his iron-on transfer method for embroidery patterns that same year in his home country of England. On October 14, 1879, his agents in the United States received an American patent for the process.

In 1895, Briggs & Co. was incorporated by John’s son William as William Briggs & Co., Ltd., which became famous after World War I for its traced linens and heat transfer printing patterns. That company was, in turn, absorbed into Coats, still in existence today as a thread manufacturer, in 1939.

Briggs & Co.’s Patent Transferring Papers, Patented for the United States of America is call number Trade Cat .B8528 188- in the Hagley Library’s collection of trade catalogs. You can find the manual online now in that collection’s page of our Digital Archive, as well as along with similar materials in our digital collection of 19th and early 20th century women’s handicrafts, a digital collection of materials documenting American women's participation in household handicrafts in the 19th and early 20th century.

It was commonly expected that these women would take up such crafts as part of their domestic duties, particularly needlework, a skill set most of them would begin training in as young girls. Some contemporary feminist critics considered this work to be a frivolous use of women's time and a waste of their intellectual capacity. In Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, the author argued that needlework limited the potential of young girls by stifling their minds and instilling an obsession with ornament over matters of import.

For other women, however, such work provided rare opportunities. Household handiwork could offer outlets for artistic self-expression, a chance to socialize outside the home, and a way to commemorate valued emotional bonds. Women's handiwork also offered economic opportunity through the creation of personal property with real monetary value. Additionally, it opened spaces for entrepreneurial women. Many of the items shown in this collection bear the names of women who leveraged gendered expectations about household handicrafts into occupations as pattern designers, authors, and shop owners.