The 19th century represented a major time of transition in the United States. During this dawning of the Industrial Revolution, machines replaced human labor, opened new industries, and provided unique opportunities for growth. But the transition was gradual. Living, breathing machinery such as horses worked alongside steam engines and electrical generators for decades. Horses were critical to the development of America’s mixed industrial and agricultural economy as well as its bustling urban landscapes.

Horses and other draft animals could go places and do things that machines could not. Machines were heavy, required skilled maintenance, a shop for fabricating parts, fuel, and lubrication. Horses, on the other hand, needed minimal care, shelter, and equipment. Some fodder or a patch of grass for grazing fueled a strong, obedient, patient, and powerful engine. Being self-propelled, horses scaled mountains, descended into valleys, forded rivers, and fit in narrow woodlands, towpaths, and mine shafts. While a machine could easily out-work a human or a horse, it would be quite a while before it was a better option.

By 1890, there were about 13 million horses in the United States—two million of which worked in cities—and their population would not peak until around 1910. It is estimated that there were 150,000 horses in New York City alone! Without them, city life would be impossible. They transported people and things to every corner of the city. They hauled raw materials and finished goods to and from the docks and railways. They stocked warehouses, markets, and homes. They removed trash, towed fire engines, and pulled elaborate funeral carriages. But there was a tradeoff. While their labor was the lifeblood of the city, each horse littered the streets with up to 45 pounds of manure and two gallons of urine a day.

The life of a horse in a city was hard and short. Not many lived more than a few years. Stables were poorly maintained and spread disease. Horses worked in the stifling heat and humidity of summer and in the bitter, icy winters. Their owners and drivers pushed them beyond their reasonable physical limits. When they died, their massive corpses were left to rot in the streets until decomposition made their remains easier to remove.

Still, in the late 19th century, people’s attitudes regarding animals began to change. Americans developed a growing sense of responsibility towards animals and believed they deserved the same humane care and respect as people. The mistreatment of horses and other animals inspired Henry Bergh to found the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in New York City in 1866.

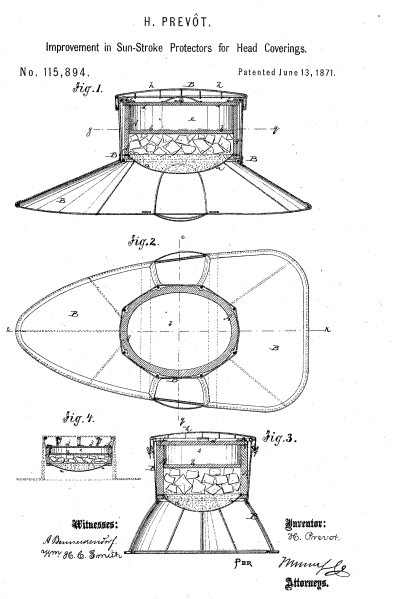

This shift also inspired inventors to create new products to properly feed, protect, and care for animals. Hagley’s patent model collection reflects this trend and has many examples. Perfect for the approaching summer season is this unique hat.

Made of lightweight silk on a metal wire frame, the crown of the hat serves as a compartment for holding ice. Lined with insulating rubber, the ice would cool the user while a layer of sawdust beneath the compartment absorbed condensation “to prevent the moisture from reaching the head and injuring it.” Though the inventor claimed that it was designed “to cool the heads of men and animals during hot weather”, notice the oval slots on either side that would allow it to sit perfectly on the heads of animals with long ears like horses.

The inventor was a German immigrant named Hellwig Prevot (1826-?). A carpenter by trade, he arrived in New York City the same year the ASPCA was founded in1866. His wife and children remained in Germany. Many immigrants came alone and sent money to support their families or to help pay for their passage. As many as one in three, having earned a tidy sum working here in the United States, returned to their country of origin. Prevot might have done so. He continued working as a carpenter, eventually moving to Cincinnati, Ohio, but nothing can be found of him after 1897.

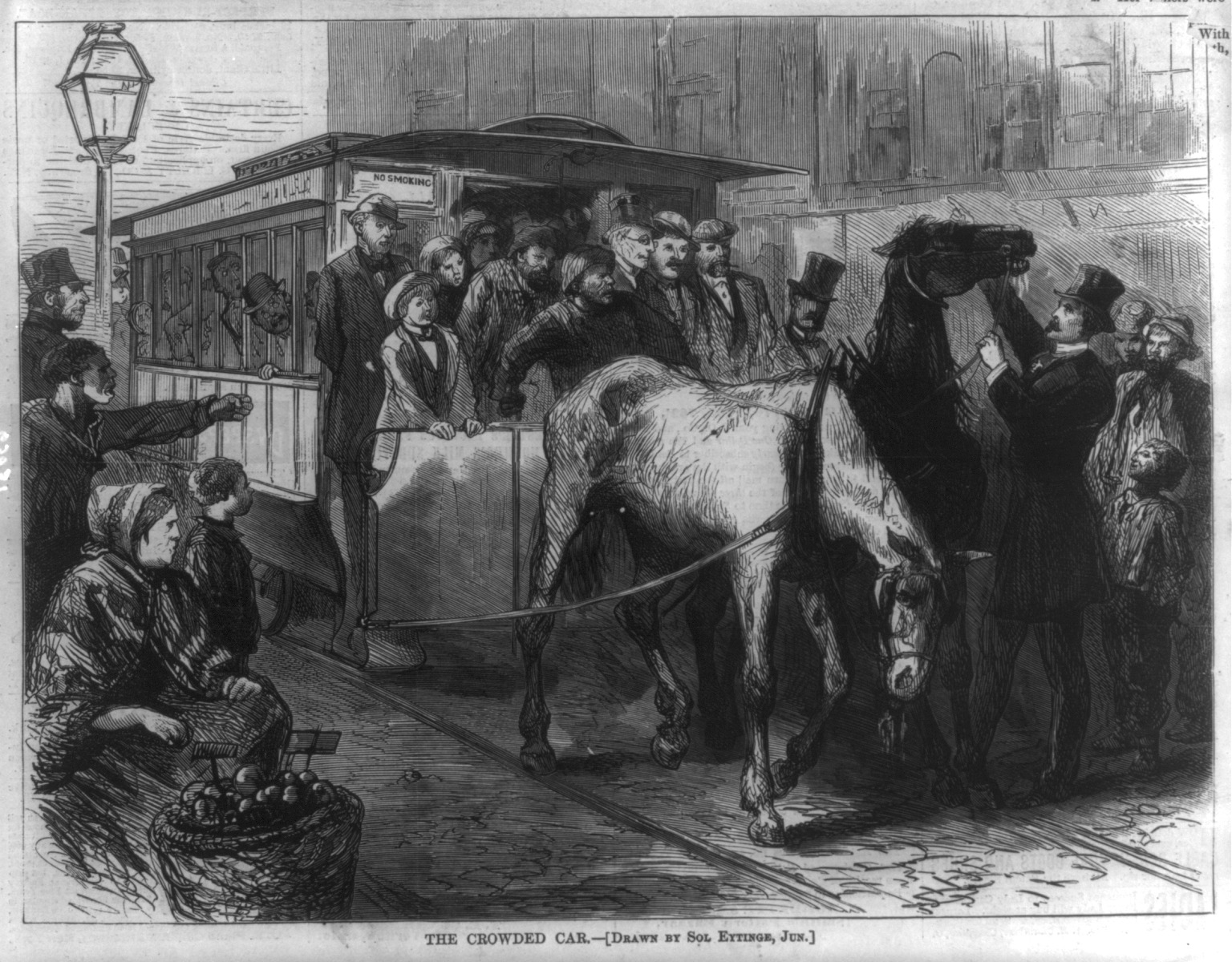

Prevot’s motivation for inventing such a hat is anyone’s guess. He most likely did not own a horse. A carpenter in New York City in the 1870s earned only about a dollar and a half a day while a basic draft horse cost about $150, which was beyond his income. Besides, he did not even need a horse. Most city dwellers traveled on foot or on trolleys or street cars—towed by a horse, of course! Even today, many New Yorkers find cars, the horse’s modern equivalent, too expensive and impractical.

Perhaps it seemed like a useful idea, and he hoped it would be profitable. But there is no evidence that these hats were made and sold. Maybe he could not find enough buyers or attract investors. Sadly, like most of the inventions represented in Hagley’s patent model collection, it is another unrealized dream that never made it beyond the imagination of its inventor.

Be sure to visit this patent model this summer near the entrance to Nation of Inventors, Hagley’s permanent exhibit celebrating American invention and innovation featuring over one hundred patent models.

Chris Cascio is the Alan W. Rothschild Assistant Curator, Patent Models at Hagley Museum and Library