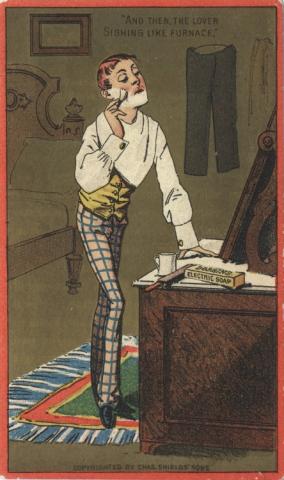

Today's #TradeCardTuesday brings us this ca. 1880? advertisement for Dobbins' Electric Soap, manufactured by Philadelphia's Isaiah L. Cragin & Company (est'd 1867).

The brand's name was bestowed upon it by its original manufacturer, John B. Dobbins, a Philadelphia soapmaker who presumably appended the u2018Electric' to his product to capitalize on popular enthusiasm for the promise of electrification. Dobbins was also the manufacturer of Dobbins Medicated Toilet Soap and Dobbins Electric Boot Polish.

Dobbins appears to have temporarily lost the rights to the soaps that bore his name in 1869, along with use of his trademarks, manufactory, and the materials within it for a period of twenty years as a result of debts owed to Charles I. Cragin, the son of Isiah L. Cragin. This agreement would later result in a vicious court case. In 1890, rather than relinquish the use of the name as their legal agreement required, the Cragin family continued to make use of Dobbins' brands and trademarks, and even incorporated in New Jersey as the Dobbins Electric Soap Manufacturing Company. Dobbins, described by J. Warren Coulston, the lawyer who drafted the original agreement as "very old" and "very poor", chose to pursue the matter.

Ultimately, the New Jersey courts were unimpressed with the Cragins' argument that the contract's statement that "they may use his name upon and as descriptive of any soap or blacking they may hereafter make u2026" nullified term limits outlined elsewhere and gave them perpetual rights to the name and trademarks. John B. Dobbins won the case and was awarded nearly one million dollars in royalties that had been denied to him.

It's not clear from newspaper accounts whether Dobbins was able to collect those funds, however. By 1895, his soap works at the corner of Susquehanna and Germantown Avenues in Philadelphia were in use by the Quaker City Chocolate Works, later known as the Quaker City Camden Company. Dobbins died not long after, on May 17, 1898 in Camden, New Jersey at the age of 68. The site of his soap works is now a vacant lot. The Cragins, meanwhile, retained operations of the Dobbins Soap Manufacturing Company and continued to use the brand name in advertisements denouncing similarly named products as "mediocre" imitators whose products would "rot and ruin clothes".

Isiah, the elder Cragin, died on October 2, 1901. Charles I. Cragin, by then a wealthy man, who had also inherited his wealthy father's estate, appears to have spent the rest of his life as president of the company and employed as a director of Philadelphia's Fourth Street National Bank, though his December 16, 1915 obituary in the city's Evening Public Ledger noted that he "devoted little time to either enterprise in the last 20 years", preferring instead to entertain guests in his home in Philadelphia and in Reve D'Ete, his lavish vacation home in Palm Beach, Florida often described in the society pages as "the most luxurious of semi-tropical palaces" and which, in 1891, was touted as the "furthermost south mansion in the United States".

The Dobbins Soap Manufacturing Company, located at 17th Street and Federal Street, remained in the hands of the Cragin family until 1934, when it was purchased by the Iowa Soap Company. By 1959, the Concord Chemical Company called the manufactory home, remaining there until the late 2000s, when the Concord Chemical Company manufactory became the abandoned Concord Chemical Site. Following intervention from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agencyin 2010, the site was burned to the ground in a fire on June 19, 2011. In 2018, the former president and CEO of the by then defunct Concord Chemical Co. was sentenced to six months of home confinement for illegally storing and abandoning hazardous, corrosive, and ignitable waste at the facility.

This trade card is part of Hagley Library's Carter Litchfield collection on the history of fatty materials (Accession 2007.227). As an organic chemist, Carter Litchfield (1932-2007) studied and specialized in edible fats. Over the course of his career, Litchfield built an important collection about the history of fats and fatty materials. This collection has not been digitized in its entirety. The online collection is a curated selection of items and primarily includes paper ephemera such as ration stamps, tax stamps, trade cards, pamphlets, and trade catalogs. You can view it online now by clicking here.