In my earlier Research News installments from October and November 2022 and 2024, I wrote about the now-defunct practice of laminating documents for preservation. I noted that Hagley holds a number of historic paper maps, artworks, and other important items that were laminated—a process of sealing or attaching paper between layers of cellulose acetate film. In this third article on lamination, I focus on a particular historic map that needs necessary but expensive conservation work.

from October and November 2022 and 2024, I wrote about the now-defunct practice of laminating documents for preservation. I noted that Hagley holds a number of historic paper maps, artworks, and other important items that were laminated—a process of sealing or attaching paper between layers of cellulose acetate film. In this third article on lamination, I focus on a particular historic map that needs necessary but expensive conservation work.

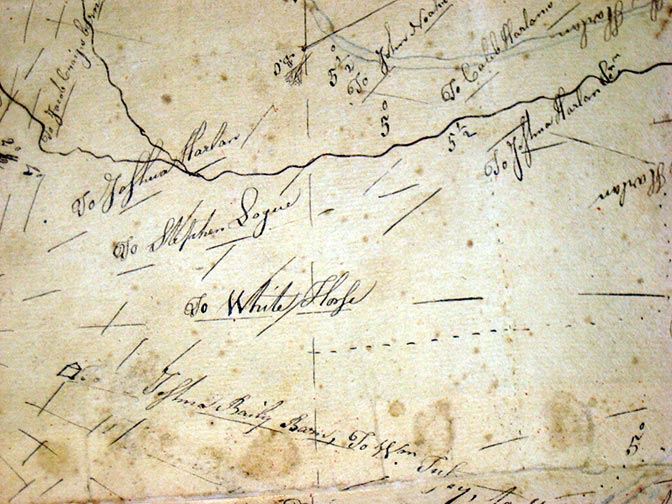

Earlier this year, we brought one of the Library’s laminated items to the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia for assessment and a treatment estimate. The item is a hand-drawn map from 1795 showing the areas of Yorklyn, Delaware, and Kennett Square and Glen Mills, Pennsylvania (map detail in image on right). Created by mapmakers John Harlan and Sam Sharp, the map documents borders, landowners, and regional landmarks of Delaware and Pennsylvania. Delaware declared independence from Pennsylvania in 1776—the same year the American Colonies declared independence from Great Britain and just twenty years before this map was made.

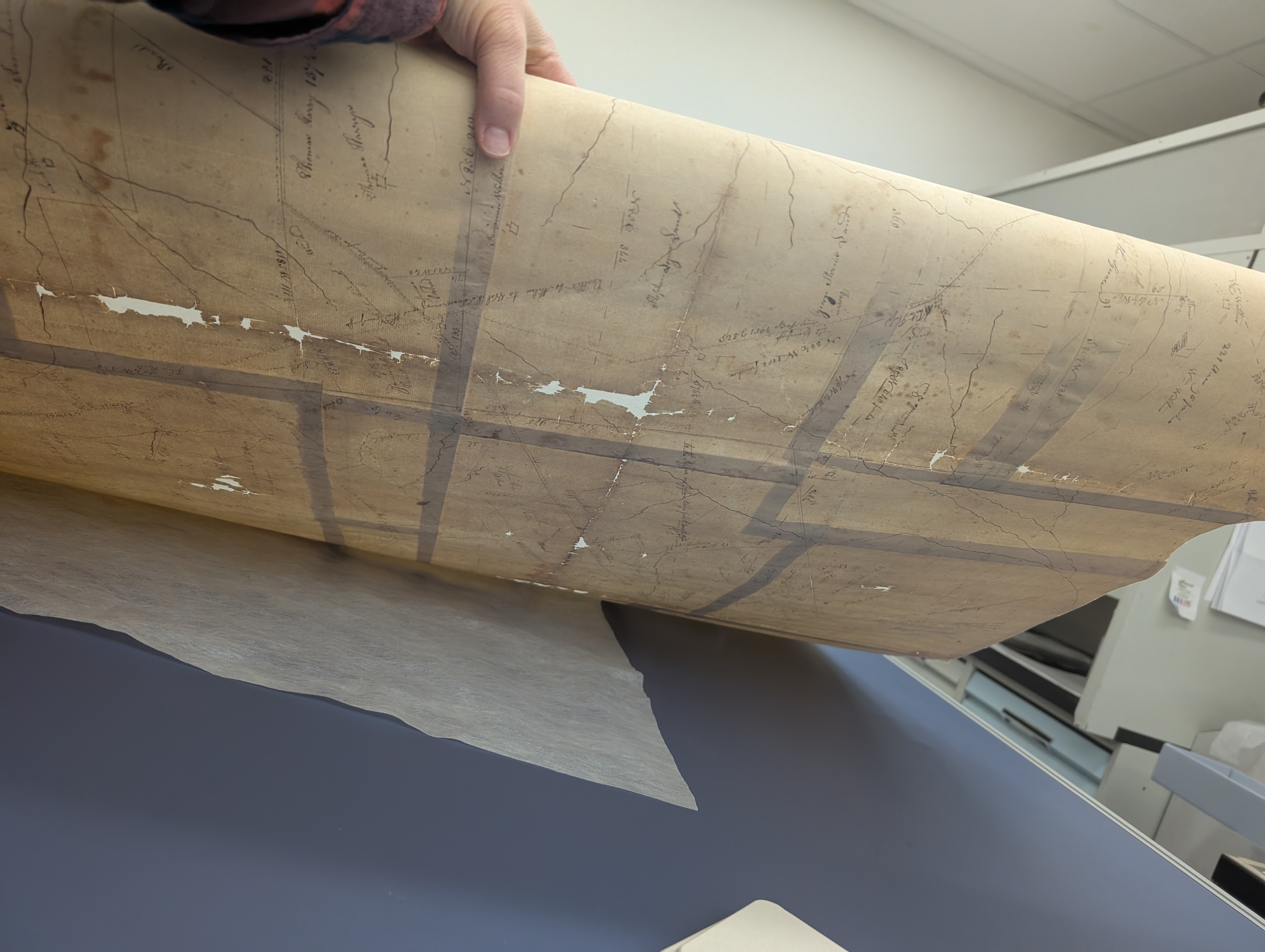

The map consists of roughly two dozen sheets of paper attached together through lamination. Originally, paste or dough seals served as the adhesive, but these were most likely removed during the lamination process. Measuring about five square feet, the map was stored rolled for decades because of its size. Over time, the plastic laminate has begun to age and shrink, making it impossible to lay the map flat without risking tears. It contains writing and additional information on both sides, so the deteriorating lamination, the map’s size, and our inability to safely unroll it all hinder efforts to read the handwriting. A thin tissue layer added during lamination has also produced a slight haze over the inks. The solution is to remove the old lamination layers with solvents and separate the individual sheets of paper to facilitate storage. During the process, the original arrangement of the parts will be thoroughly documented If we can also digitize it with a high-resolution camera, even better.

The map consists of roughly two dozen sheets of paper attached together through lamination. Originally, paste or dough seals served as the adhesive, but these were most likely removed during the lamination process. Measuring about five square feet, the map was stored rolled for decades because of its size. Over time, the plastic laminate has begun to age and shrink, making it impossible to lay the map flat without risking tears. It contains writing and additional information on both sides, so the deteriorating lamination, the map’s size, and our inability to safely unroll it all hinder efforts to read the handwriting. A thin tissue layer added during lamination has also produced a slight haze over the inks. The solution is to remove the old lamination layers with solvents and separate the individual sheets of paper to facilitate storage. During the process, the original arrangement of the parts will be thoroughly documented If we can also digitize it with a high-resolution camera, even better.

We do not know exactly why the map is part of Hagley’s collection, but we do know that avid collector Pierre Samuel (P.S.) du Pont—founder of the Hagley Library and Longwood Gardens—acquired it. He likely collected the map because of his interest in the region around Longwood. We know for certain that he owned it in 1951, thanks to correspondence located by our Foundation Archivist, Marsha Mills. The earliest letter she found refers to materials "in a plastic sheath," almost certainly describing the lamination.

In 2025, Marsha discovered an even more detailed reference: a request for treatment of an “old chart… a survey made by Harlan in 1796 of Chester County, Pa. and of New Castle County in Delaware.” This appeared in a 1951 letter written by P.S. du Pont to Leon de Vallinger of the Delaware State Archives—a very interesting and informative clue.

Although the map contains writing dated 1795, the letters about its treatment refer to 1796-likely a typographical error.

When staff from the Delaware State Archives visited Hagley this year, I shared the 1951 letter with them. They searched their records and produced the companion letter discussing delivery and treatment of the map. They also provided a historical instruction manual outlining the materials and methods used for laminating documents at the Delaware State Archives in the early to mid-20th century. Their website even features a few photographs of the hot press that was used. With this evidence, we can now say with confidence that the 1795 map was laminated by the Archives’ staff about seventy-five years ago.

Not surprisingly, removing the lamination is both complicated and expensive. Because the work requires large quantities of acetone and other volatile solvents, we sent the map for a professional conservation assessment. Hagley does not currently have the necessary fume hood or equipment to treat an item of this size. Removing the laminate and stabilizing the map—eliminating the acids released by the aging plastic—is a priority. The total cost for this treatment is estimated at $13,000. Without this treatment the map will deteriorate and its valuable information lost. We hope you will support the preservation of this map through a donation to the Hagley Library’s Conserve-a-Book Fund.

If the lamination is removed, our staff can digitize this significant document and add it to the Hagley Digital Archives, making it available to everyone. Broader access will surely bring forward new stories about the map and its connections to the nation’s founding and to land use in the early American republic.

For more information on Library collections support opportunities, please contact Hannah Spring Pfeifer, Library Coordinator, at hpfeifer@hagley.org.

Laura Wahl is the Library Conservator at Hagley Museum and Library