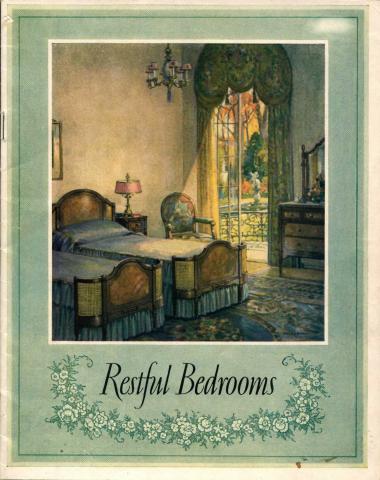

We're posting this 1930 catalog for bedroom furniture today on account of Sarah Elisabeth Goode (1850-1905), one of the first Black women to be issued a U.S. Patent in her own name on this date, July 14, in 1885.

Goode's patent, No. 322,177, was for a cabinet with a fold out bed that could be used during the day as a desk, a precursor to the Murphy bed, which was invented in 1900.

After being freed from slavery by the end of the Civil War, Goode moved to Chicago, where she and her her husband Archibald opened a furniture store.

Goode's invention was timely; housing in cities like Chicago was becoming increasingly crowded. Her invention was a direct response to complaints from customers looking for furniture that would address the problem of saving space in tight quarters.

Goode was preceded by other inventors, including Judy Woodford Reed (c.1826-c.1905), whose Patent No. 305,474 for a "Dough Kneader and Roller" was awarded on September 23, 1884 and was signed with an X, indicating that she was likely unable to read or write; as well as Martha Jones, who was granted U.S. patent No. 77,494 on May 5, 1868 for an improved threshing machine for corn.

It is likely these women were joined by others - since patents didn't record data about the race or gender of inventors, many women filed inventions using initials, and the identity of early inventors is often a mystery.

Other women were denied patent rights due to the law; in the many states where women were disallowed from owning property prior to 1900, this often extended to intellectual property, require the inventions of women to be patented in the name of husbands and other male relatives.

Additionally, patent law surrounding enslaved people largely allowed enslavers to take credit for the inventions of the people they held captive.

This changed on June 10, 1858, when the the U.S. Attorney General ruled that neither the slave or the slave owner could claim credit for inventions, declaring that the slave owner could not rightfully take the patent oath claiming invention (as it would be a lie) and neither could the enslaved person, as they were not considered citizens of the United States in the aftermath of the Supreme Court's ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

To view this catalog from the Simmons Company (item ID 08061710 in Hagley Library's collection of trade catalogs and pamphlets) online now in our Digital Archive, just click here.