When first contacted about MCI, William McGowan set to work learning everything he could about the communications industry. He read through thousands of pages of Federal Communications Commission (FCC) testimonies and hearings. His reading revealed that AT&T was a de facto monopoly regulated by the government, and he believed that there was a need for a specialized common carrier like MCI.

Further reading convinced McGowan that the FCC was moving toward competition in the telecommunications industry. McGowan joined MCI in 1968 and recognized the potential for a nationwide microwave system. Taking MCI national was finally the challenge McGowan had been waiting for.

Jack Goeken (1930- ) submitted the initial application for permission to build a private line microwave system in 1963. Goeken designed his system on a route from St. Louis to Chicago to provide truckers a way to access telephone lines through their radios. MCI faced skeptical FCC commissioners and opposition from AT&T and Western Union. AT&T argued there was no need for MCI’s service; they also argued that, in order to compete with proposed MCI routes, AT&T would have to raise their rates.

AT&T used a rate averaging system; calls between areas of similar distance were billed the same, regardless of actual transmission costs. This system allowed sparsely populated areas to enjoy the same low phone rates as high-volume, major cities.

After hearing arguments from all three parties, the FCC board deadlocked at 3-3. The appointment of a seventh commissioner loomed as the potential tie-breaker. After the commissioner was named, MCI set out on an aggressive lobbying campaign, a tactic they used with great success in later years. Ultimately, the FCC voted to approve MCI’s application.

The early years at MCI were filled with uncertainty. Even after the FCC decision allowed MCI to expand, there was constant doubt that the company could grow quickly enough to become competitive with AT&T.

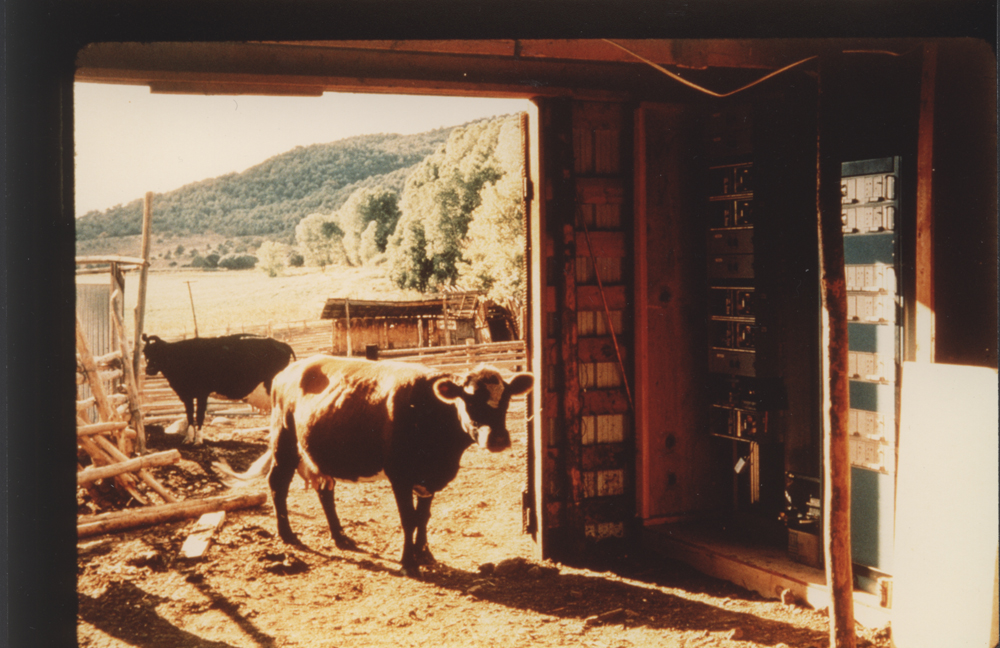

After MCI received approval to begin construction, McGowan knew the company had to work fast. AT&T challenged every move MCI made, and there was the threat that the FCC would order MCI to halt construction. MCI also had to work inexpensively since they did not have the financial resources of AT&T.

While AT&T would buy an entire farm to build a tower, MCI would negotiate for only the use of the space needed for the tower and equipment shed. When one landowner refused to allow tower construction, the MCI construction crew offered to decorate it every Christmas (she finally agreed). The MCI construction crews thought of themselves as pioneers; they often slept on-site in their trucks and raced to see how quickly they could put up a tower.

McGowan hoped to foster a similar sense of excitement in the MCI offices. He encouraged employees to work hard and take risks, even if failure resulted. He also wanted employees to feel free to come and go with MCI as they pleased.

While working at Shell, McGowan saw that employees could not leave one oil company to go to another, and companies agreed not to hire from other companies to avoid poaching. McGowan saw this as yet another way that workers became frustrated and felt trapped in their position. At MCI, however, any employee could leave for another job opportunity at any time, and the employee would be welcomed back if he or she decided to return.

In order to recognize employee achievements and maintain morale, MCI created "Excellence in Service." Each year, MCI management selected deserving employees and sent them on a three-day retreat featuring awards, guest speakers and entertainment.